Muqarnas

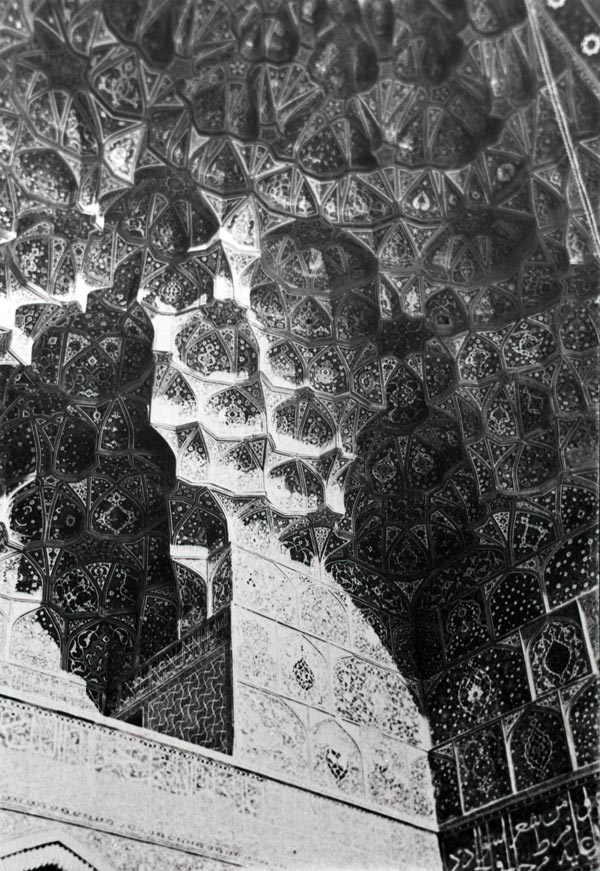

Figure 1. Interior view of the muqarnas dome Shrine of Shaykh ‘Abd al-Samad, Natanz, Iran, 1304-5 CE Visual Resources Collections, Department of the History of Art University of Michigan, 23.5

Muqarnas, sometimes referred to as stalactites, are pointed niches arranged in tiers that appear to form a honeycomb or staircase. They are a signature decorative element of Islamic architecture, in which they fulfill both functional and ornamental purposes. This architectural structure, which serves to transition from a square base to a circular dome, developed around the tenth century in Iran and Iraq, penetrating North Africa sometime during the eleventh century.5 Muqarnas also create optical illusions that add depth to an architectural space by playing with light cast onto the intersecting facets, as can be seen in the Shrine of Shaykh ‘Abd al-Samad in Natanz, Iran (Figure 1).6 This shrine was constructed during the early fourteenth century to mark the grave of a Sufi shaykh who died in 1299 CE. The muqarnas ceiling captured in Pope's photograph shows the rippling facets as they cascade down the interior of the shrine's conical dome.

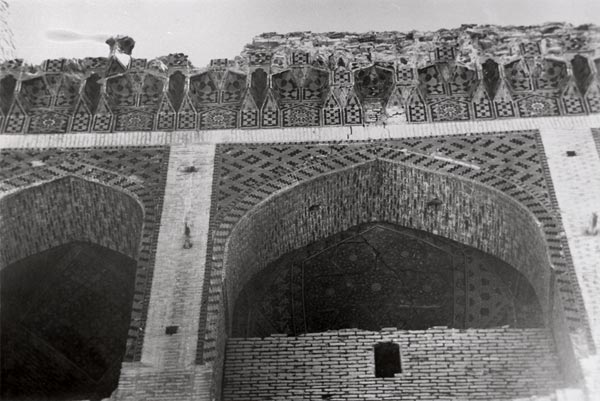

Figure 2. Muqarnas cornice decorated with tile mosaic work Tomb of Öljeitü, Sultaniya, Iran, 1302-12 CE Visual Resources Collections, Department of the History of Art University of Michigan, 21.36

Muqarnas are used in domes, niches, arches, and friezes. Another early example of muqarnas is found in a horizontal decorative cornice that ornaments the Tomb of Sultan Öljeitü built in 1302-12 CE (Figure 2).7 In the photograph, the frieze displays one extant tier of tiled niches above the second-story archways that frame the arcade. This Ilkhanid mausoleum stands isolated in the ruins of the once flourishing city of Sultaniya. As its crowning glory, the tomb showcases architectural knowledge and practice in medieval Iran. On its exterior, the royal tomb was lavishly decorated with tile mosaic work.8 Cut-tile pieces were fitted to create a variety of floral and geometric patterns; these also were applied to the cornice of muqarnas as recorded in Pope's photograph and the fragment included in the exhibition.

Figure 3. Muqarnas pendentive with faience Mosque of Gawhar Shad, Iran, 1416-1418 CE Visual Resources Collections, Department of the History of Art University of Michigan, 49.4

The Timurids ruled over Iran and Central Asia after the Ilkhanids, whose architectural achievements they inherited and innovated upon over the course of the fifteenth century. The Timurids are best known for their monumental structures and their novel decorative treatment of buildings, especially their interiors.9 For example, the Mosque of Gawhar Shad displays a daring use of muqarnas in its pendentives (Figure 3). Typically, where a circular dome meets the walls of a square-shaped foundation, the transition zone must be developed in order to fill the gaps in the corners. Often squinches are used to bridge the angle between the dome and walls. In many buildings, muqarnas developed from squinches to swathe the entire interior of the dome in tiers of facets. Instead, in the Mosque of Gawhar Shad, four pendentives spring from the angles of the chamber to support rows of tiers filled with muqarnas.10 These curved muqarnas encasing the interior of the dome have a distinctly kaleidoscopic allure because of their mosaic tiles in rust, blue, and chocolate hues. In addition, the mosaic tiles are decorated with plant motifs such as winding vines, flowers, and leaves that combine to create a variety of vegetal patterns.

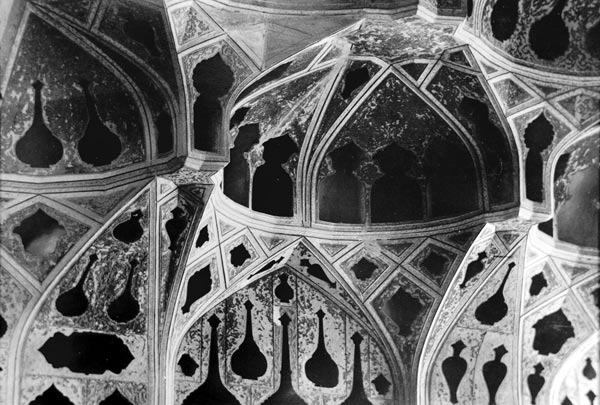

Figure 4. Pierced muqarnas detail in the chini-khana Ali Qapu Palace, Isfahan, Iran, 1501-1722 CE Visual Resources Collections, Department of the History of Art University of Michigan, 36.4a

Perhaps some of the most famous muqarnas in the Islamic world were developed under Safavid patronage in Iran (1501-1722). A number of mosques and palaces in the city of Isfahan show a bold and creative use of this particular architectural motif.11 For example, in the Ali Qapu Palace, the chini-khana (china room or music room) located on the top floor exhibits a sophisticated manipulation of light as it intersects with built form (Figure 4). Here, rays of light bounce off the painted plaster muqarnas, which are pierced in order to reveal a number of objects that were placed on display in this Safavid reception room and Kunstkammer. Without a doubt, the chini-khana is an architectural tour de force of interior design, in which decorative facets create a light-reflecting structure of geological complexity. The muqarnas are simultaneously used as interlocking display cases for the precious objects—such as flasks and dishes—Safavid rulers exhibited to their elite entourage and foreign visitors at the imperial capital. The use of muqarnas in the Ali Qapu Palace illustrates how this particular Islamic decorative design fulfilled functional and aesthetic needs while also enabling the display of power and wealth in early modern Iran.

References:

- Tabbaa 1985; Bloom 1988; and Dold-Samplonius and Harmsen 2005, 85.

- Blair 1986a.

- Wilber 1955, 92; Godard 1964, 1107; and Blair 1986b.

- Blair 1986b, 143.

- Lentz and Lowry 1989; Golombek and Wilber 1988.

- Byron 1964, 1133.

- Babaie 2008.