Gardens

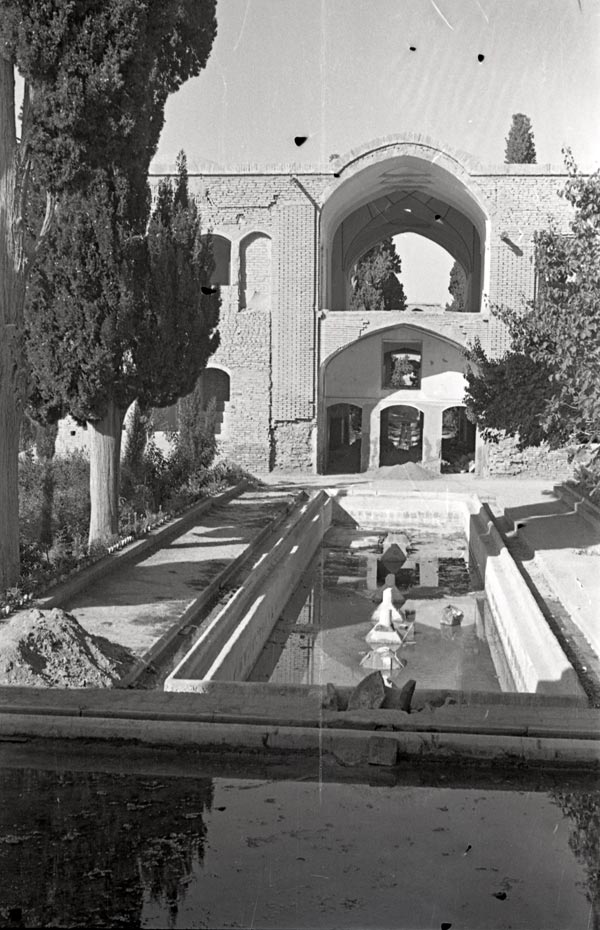

Figure 12. Exterior view of garden showing a qanat Bagh-i Fin, Kashan, Iran, 1590 CE and later Visual Resources Collections, Department of the History of Art University of Michigan, 16.7

The Islamic world is vast, and although it spans many continents with varied climates, much of it is arid—especially the Iranian desert plateaus. The gardens of Iran provide a lush and shady refuge within largely dusty and hot surroundings. Gardens are often considered "blessed escapes" that offer relief from thirst and heat.29 The primary function of the garden is thus to be a site of relaxation and recreation. While many studies of Islamic gardens focus on either their leisurely properties or their role as metaphors for heaven, gardens also served as places for political meetings, social ceremonies, and religious pilgrimages while simultaneously acting as integral elements of urban design.30

The garden Bagh-i Fin, located in a suburb of Kashan, is one of the most famous Iranian gardens. As a UNESCO World Heritage site, it is considered a national monument under the protection of the Iranian government.31 The garden is formed by a series of watercourses called qanats (Figure 12) and pools (Figure 13) that frame the buildings and garden plots. While the garden was designed during the late sixteenth century, the extant buildings were added over subsequent centuries, including its Qajar-era (1785-1925) central pavilion (Figure 14).32 The garden is square-shaped and protected by an enclosure wall that segregates it from the outside world. Within, it is subdivided into four segments by two channels that cross in the center of the complex. This quadripartite plan is referred to as a chahar bagh, meaning "four gardens" in Persian. The Islamic garden in general and the chahar bagh in particular are noted as symbolically mirroring paradise, which is often cited in mystical poetry.33 The four-part garden plan is also imitated in carpet patterns and mosaic decoration, highlighting its prevalence and popularity in Persian culture.34

Figure 13. Pool fed by a qanat Bagh-i Fin, Kashan, Iran, 1590 CE and later Visual Resources Collections, Department of the History of Art University of Michigan, 16.5

Gardens such as Bagh-i Fin are made possible through irrigation systems; the necessary waters are channeled into the gardens from underground wells or nearby springs. In the case of Bagh-i Fin, water is captured from the local Sulaymaniya spring to supply the channels and pools. The pools create sheets of water without apparent boundaries, as can be seen in Figure 13. When not outfitted with fountain jets, the pools also reflect the pavilions and surrounding vegetation, making the garden appear more dense and lush.

The qanats carry the water that stimulates the garden blooms. A garden generates three valuable resources thanks to these water channels: flowers, fruit, and shade. Hardy cypress trees line the channels in Figures 12 and 14, casting shadows on the walkways throughout the garden.35 The garden plots nourished by water are filled with a variety of flowers such as lilies, irises, eglantine, roses, jasmine, and amaranth. Alongside cypresses, Bagh-i Fin (like many other gardens) boasts almond, apple, cherry, and plum trees.36 All of a visitor's senses are enlivened by the garden: sight is overwhelmed by the vast array of colors; hearing is activated by the gurgling of fountains and streams, and the chirping of birds; smell is captured by the wafting perfume of foliage and flowers; and touch and taste are engaged by the sweet and juicy bounty provided by the crop trees.

Figure 14. Exterior view of central pavilion undergoing repair Bagh-i Fin, Kashan, Iran, 1590 CE and later Visual Resources Collections, Department of the History of Art University of Michigan, 16.3

The best example of a large formal Persian garden, Bagh-i Fin is a beautiful and relaxing site rich in history.37 While foliage is the key ecological element of a garden, the architecture within serves important purposes as well. Arthur Upham Pope and Phyllis Ackerman were among the first scholars to explore the topic of gardens and garden architecture. Their discussion in A Survey of Persian Art opened the door for future studies on the topic.38 Likewise, in 1962 Donald Wilber published the first academic monograph exclusively dedicated to Persian gardens under the title Persian Gardens and Garden Pavilions.39 However, only recently has Mohammad Gharipour, in his 2013 study on Persian Gardens and Pavilions, given garden pavilions the attention they deserve.40

The garden pavilion is the nucleus of the garden (Figure 14).41 It allows a spectator to fully enjoy the vista of the garden while remaining indoors. Garden pavilions were sites of political and ceremonial activities, which were described and depicted in many Persian poems and paintings. Often the central pavilion was used as a royal court when the shah and his entourage visited the area. Shah ‘Abbas I (ruled 1588-1629) erected the first structure in Bagh-i Fin in 1587 CE. In its role as a royal garden, Bagh-i Fin and its central pavilion likely catered to many important events over the course of several centuries. However, Bagh-i Fin became infamous for the murder of a prime minister in 1852 CE.42 After this unfortunate incident, the garden fell into disrepair, and it was not until after 1935 that it was restored.

The garden of Bagh-i Fin has undergone countless transformations and additions, like many gardens in the Islamic world. For these reasons, it is difficult to study a garden's history because of its many topographical and architectural metamorphoses. However, its function as a place of beauty and repose as well as its role in political and cultural life has remained constant, leading to its continued representation in many other art forms still today.

References:

- Pope and Ackerman 1964, 1428.

- Gharipour 2013, 2.

- Wilber 1957, 506.

- Wilber 1962, 224.

- MacDougall and Ettinghausen 1976; Moynihan 1979; and Gharipour 2013.

- Wilber 1957, 506; and Pinder-Wilson 1976.

- Moynihan 1979.

- Porter and Thévenart 2003.

- Wilber 1962, 221.

- Pope and Ackerman 1964.

- Wilber 1962; and Gharipour 2013, 4.

- Gharipour 2013.

- Pinder-Wilson 1976, 71.

- Wilber 1957, 221.