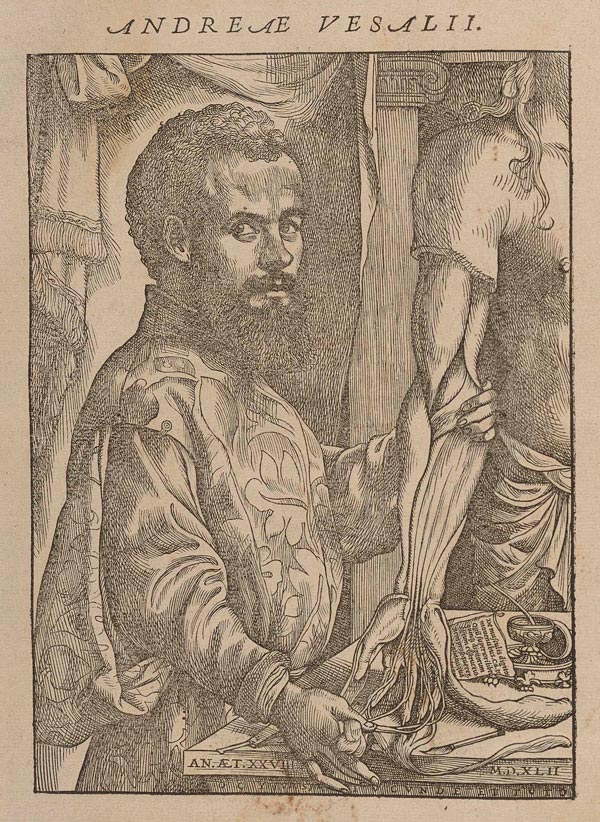

The illustrated title page of Andreas Vesalius’ De humani corporis fabrica libri septem (Basel, 1543) encapsulates the revolutionary approach to the examination of the human body in the Renaissance. As an anatomist and physician, Vesalius proudly depicts himself at the center of the anatomical theater at the University of Padua. He is performing a dissection of a female body, suggesting to the readers that his treatise is based on his own research. In the past, the physician sat on a lofty chair, teaching anatomy from a book, while a surgeon-barber performed the autopsy. Many of the books and prints on display reflect Vesalius’ spirit of medical inquiry. Whereas in the Renaissance physicians were still indebted to the Graeco-Roman medical tradition, new medical advances based on empirical research took place, opening the door to the writing of masterpieces like William Harvey’s Anatomical Treatise of the Heart and Blood in Animals (Frankfurt, 1628).

Renaissance Medicine