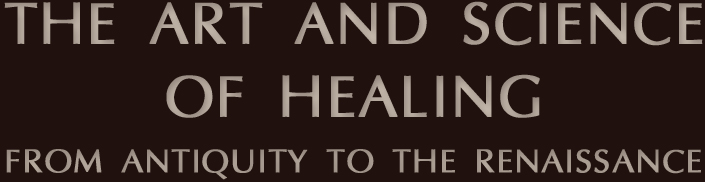

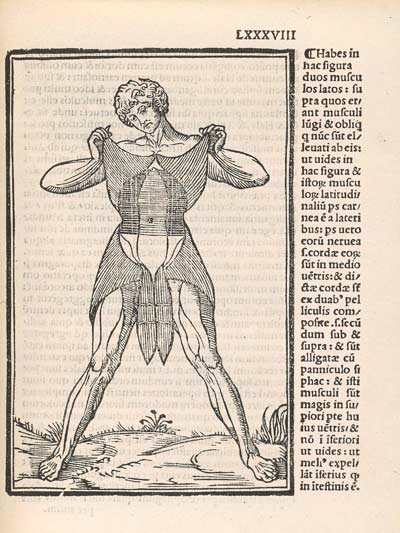

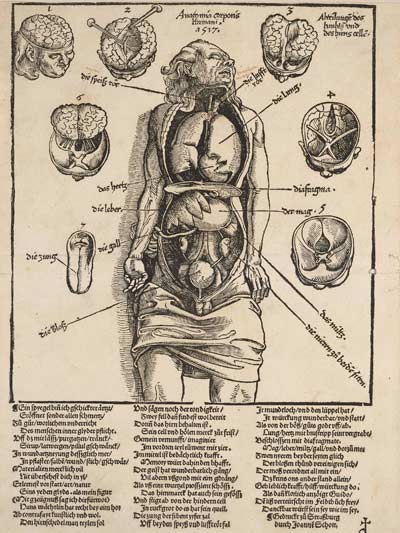

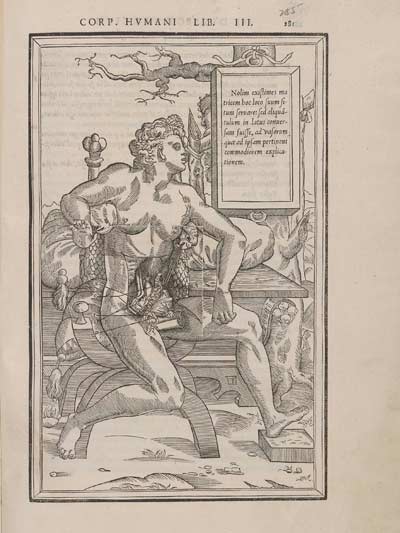

Objective knowledge about the human body could only be achieved by the practice of human dissection. In the Middle Ages, the term “anatomy” signified a teaching exercise based on the dissection of a human body. In twelfth-century Salerno, dissection was restored for the first time since early in the Hellenistic period. Initially, the animal used was the pig, supposedly because of the resemblance to the internal organs of the human body. But human dissection only began at the end of the thirteenth century, probably as a result of a close reading of what was then known as the extant anatomical teachings of Galen. At the universities of Bologna and Montpellier, and later elsewhere in Europe, human dissection began to be performed as a legal autopsy, and eventually it would be used for anatomical and surgical teaching. Manuals were then produced specifically to accompany these teaching exercises, such as Mondino de’ Liuzzi’s Anatomia, written in 1316 for the students at the University of Bologna. With the introduction of printing in the fifteenth century, scholar-physicians such as Jacopo Berengario da Carpi, Johann Dryander, and Charles Estienne, authored important treatises on human anatomy, incorporating innovative woodcut illustrations that reflected their own research.