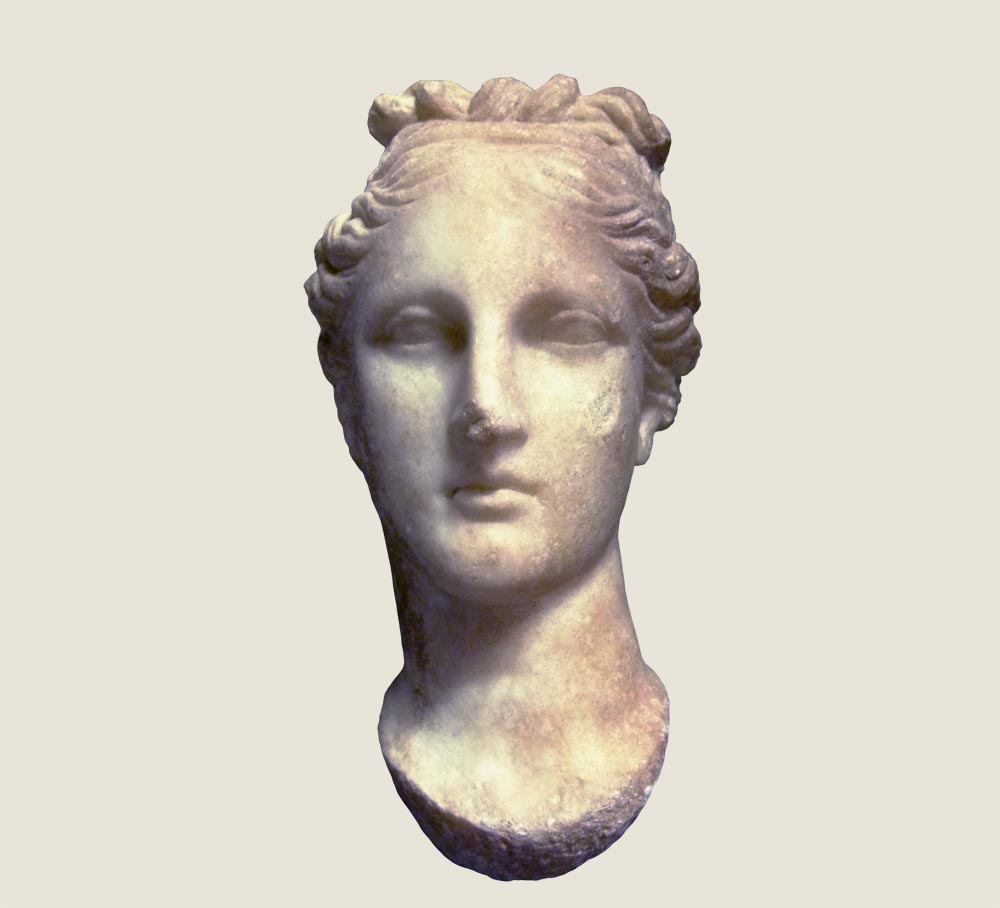

This woman wears a hairstyle that was popular in the early Julio-Claudian era, especially during the reign of the Emperor Tiberius (AD 14–37), and her facial features resemble those of imperial women of this period. She might be a member of the imperial family, but if so, her identity remains unknown. She may instead be an elite woman who chose to be portrayed in the style of the court.

This portrait of a young Julio-Claudian boy is thought to date to the period of the Emperor Claudius (AD 41–54), Nero’s immediate predecessor. Some scholars have proposed that he is the young Nero, but it is difficult to establish his identity. He could be a private individual whose image was modeled on court portraiture.