|

CAVAFY’S HOMER

Cavafy wrote poems inspired by the Homeric epics in his early years, from 1892 to 1911. Altogether at least nine Cavafy poems and one essay rework Homeric myths. Of these, “Ithaka,” Cavafy’s last Homeric poem, is a modern classic. Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis considered it one of her favorites and requested that it be read at her funeral. The New York Times then reprinted the poem, which inspired a rush of sales of Cavafy’s Collected Poems, leading to new printings and new English translations.

Cavafy’s poetry changed through the course of writing the Homeric poems. At first he set old stories to modern verse. Gradually, the contours of the myths became vaguer, the treatment of the stories more abstract. In “Ithaka,” instead of trying to “continue the sentence that Homer decided to end,” as he put it, Cavafy addressed the hero before the journey, to advise him of the dangers that might lie ahead. Cavafy completed “Ithaka” in 1911, the year he claimed to have found his voice. After that, he abandoned classical myths and turned to lesser-known historical subjects from the Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine eras or to situations he knew from his own times.

Cavafy’s Homeric writings include:

- “Priam’s Nocturnal Journey” (1893)

- “Second Odyssey” (1894)

- “The End of Odysseus” (essay of 1895)

- “The Horses of Achilles” (1897)

- “When the Watchman Saw the Light” (1900)

- “Trojans” (1900)

- “Interruption” (1901)

- “Unfaithfulness” (1904)

- “The Funeral of Sarpedon” (1908)

- “Ithaka” (1911)

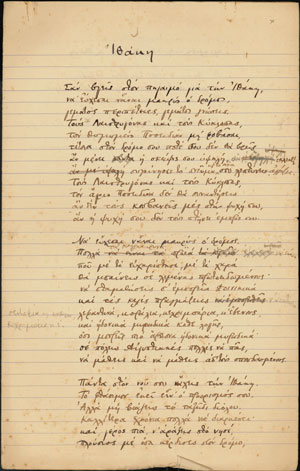

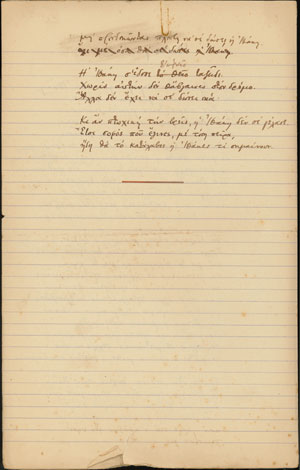

Undated working manuscript of “Ithaka” in Cavafy’s hand

Cavafy Archive, S.N.H.

|

|

Glass unguentarium

Roman

Kelsey Museum 1968.2.244 |

|

Carnelian necklace

Dynastic Egypt

Kelsey Museum 88731

|

|

Ithaka

As you set out for Ithaka

hope the voyage is a long one,

full of adventure, full of discovery.

Laistrygonians and Cyclops,

angry Poseidon—don’t be afraid of them:

you’ll never find things like that on your way

as long as you keep your thoughts raised high,

as long as a rare excitement

stirs your spirit and your body.

Laistrygonians and Cyclops,

wild Poseidon—you won’t encounter them

unless you bring them along inside your soul,

unless your soul sets them up in front of you.

Hope the voyage is a long one.

May there be many a summer morning when,

with what pleasure, what joy,

you come into harbors seen for the first time;

may you stop at Phoenician trading stations

to buy fine things,

mother of pearl and coral, amber and ebony,

sensual perfume of every kind—

as many sensual perfumes as you can;

and may you visit many Egyptian cities

to gather stores of knowledge from their scholars.

Keep Ithaka always in your mind.

Arriving there is what you are destined for.

But do not hurry the journey at all.

Better if it lasts for years,

so you are old by the time you reach the island,

wealthy with all you have gained on the way,

not expecting Ithaka to make you rich.

Ithaka gave you the marvelous journey.

Without her you would not have set out.

She has nothing left to give you now.

And if you find her poor, Ithaka won’t have fooled you.

Wise as you will have become, so full of experience,

you will have understood by then what these Ithakas mean.

Trans. Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard

|

|

|

|

Glass unguentaria

Roman

Kelsey Museum 1968.2.184 and 1968.2.246 |

|

Bronze horse

Luristan, Iran

9th century AD

Kelsey Museum 1966.2.2

|

|

The Horses of Achilles

When they saw Patroklos dead

—so brave and strong, so young—

the horses of Achilles began to weep;

their immortal nature was upset deeply

by this work of death they had to look at.

They reared their heads, tossed their long manes,

beat the ground with their hooves, and mourned

Patroklos, seeing him lifeless, destroyed,

now mere flesh only, his spirit gone,

defenseless, without breath,

turned back from life to the great Nothingness.

Zeus saw the tears of those immortal horses and felt sorry.

“At the wedding of Peleus,” he said,

“I should not have acted so thoughtlessly.

Better if we hadn’t given you as a gift,

my unhappy horses. What business did you have down there,

among pathetic human beings, the toys of fate.

You are free of death, you will not get old,

yet ephemeral disasters torment you.

Men have caught you up in their misery.”

But it was for the eternal disaster of death

that those two gallant horses shed their tears.

Trans. Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard

|

|

|

|

|

|