Inspiration

CR: Your paintings clearly engage, in one way or another, in a dialogue with the past. Classicists use different words to talk about these kinds of dialogues, such as “reception,” a catch-all term that refers to any kind of engagement with earlier traditions, from Raphael’s School of Athens to Heaney’s “Actaeon” to the kinds of academic practices embodied by departments of classical studies and museums of archaeology. In the most general sense, reception subsumes all the ways we comprehend the past, in art and literature as well as scholarship. The term I have chosen for the title of your exhibition is “Memory,” which I use to refer to the active process by which people establish and renew their links with the past, for example, through visits to “memorials,” or to sacred places, or, once again, to museums. You told me in an earlier conversation that you draw “inspiration” from ancient sculptures. What is it that inspires you, and why do you turn to the past?

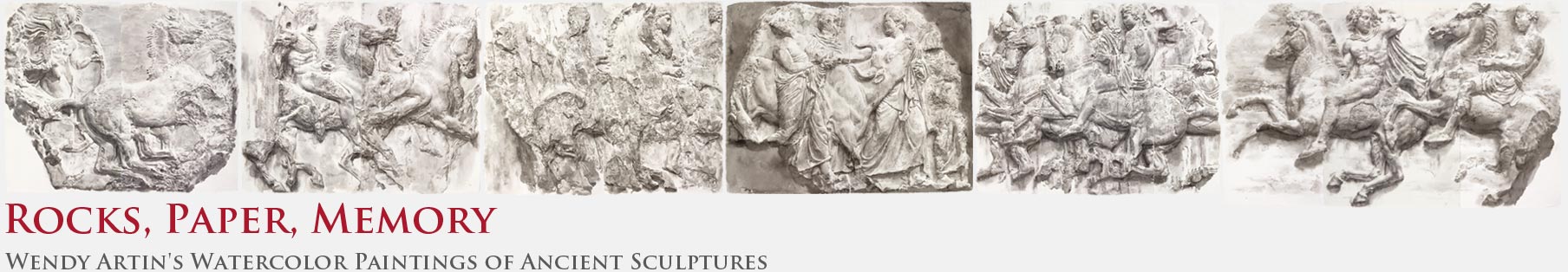

WA: When I was a child, my parents often brought me to museums, and drawing the statues was a way of keeping myself entertained. Later, during art school and beyond, I continued to seek refuge and concentration in the stillness of museums. Painting statues “en plein air” was a way of painting my favorite subject matter, people, while also being outdoors. As time went by, I simply grew more and more curious about the statues, eventually developing thematic projects. Painting statues has been a bit like living in a foreign country or learning to use watercolors: at first you arrive and see the superficial, then bit by bit, with immersion, you become more and more interested, refined, curious, enamored.

Sitting in the stillness of a museum and drawing is a long, slow and tactile process, while everyone else ducks in and out, takes a snapshot. My pictures are nostalgic: I am trying to evoke the statue, and also all of the emotions and responses that the statue itself evokes. Painting is a way of slowing down and taking possession while creating the thin transportable expression of one’s vision, which is the drawing. It is magical to watch the image emerge from the materials, to see the illusion start to happen. It is always thrilling to watch other people draw and paint too, to watch the image emerge, to see how they are seeing. I love when classes paint from my paintings, and when people tell me that they saw something that I would want to paint, because this means that they have come to see it through my eyes.

I paint pictures of ancient statues because I find them beautiful. They have a level of simplification of the human form that is neither too polished, smoothed, or rounded nor too ruggedly naturalistic. They are an exquisitely harmonious blend of naturalism and stylization, abstracted by the erosion of time. The statues are for me both familiar and universal: as close to you as they are to me, as intimate for you as they are to me.