Urban Walls

CR: When I first got to know your painting, you were working on a series of colorful watercolors of urban walls in New York, Paris, Rome: images of the kinds of accidental collages—of graffiti, torn and faded posters, peeling paint and cracked stucco—that one sees on the side streets of cities around the world. What inspired you to turn from these images to the monochrome paintings of ancient sculptures featured in this show? Is there a connection between these two series?

WA: There is a magical moment when the paper suddenly loses its flatness and frontality, and becomes space and illusion. My paintings of walls have a shallow depth of field, a bas-relief depth, just about the same as the Parthenon frieze. The level of illusion I try to achieve is that of reality moving in and out of painting, neither photo-realistic nor abstract, the freshness of watercolor brushstrokes, combined with the illusion of depth.

Years ago in Paris I wanted to make pictures of street scenes to bring home at the end of the year. Each time I sat down to paint the streets, I ended up barely indicating the streets and the buildings but greatly enjoyed painting the cars: I returned home with a series of Deux Chevaux paintings. I went on to sit in many parking lots, grimy and hidden between parked cars, painting vehicles for a few years. Eventually, I noticed that the cars I wanted to paint were parked in front of beautiful walls, and the walls grew more interesting than the cars. I eliminated the cars, went to New York, and started to paint typical downtown walls with standpipes. My favorite walls were the most deeply layered, with three-dimensional architectural detail, stains, signs, graffiti, stencils and posters of appealing images, people, and words. SoHo in the late 1980s and ’90s was full of those walls, full of people pasting and tagging and putting up personal art projects that were fun to paint. I developed a long and involved process for painting the posters so that they seem to be stickers pasted onto the painting. I selected walls whose colors I could adapt to my latest favorite tubes of watercolor. I played games with the paint, soft here, crisp there, green where an impossibly bright shade of red created an optical illusion. The wall paintings are as much about experiencing the city as they are about the paintings. They are a great way to travel and to spend the day outdoors. Each different city has a different flavor of walls, a different signature, reflecting the interests and lives of the people who live there.

During these same years, in wintertime and on rainy days, I always worked from statues and figures, in streets, museums, and studios. With statues, as with walls, I often feel that I am lingering over something that is usually passed by, something whose visual richness was created both by people and by the passage of time.

Live Models

CR: Once I met you at a studio in New York where you were just finishing up a life drawing session. That was an unusual experience for me as an archaeologist and historian of ancient art. We spend a lot of time looking at statues of nudes, but we are seldom confronted with live models—although of course the Greek and Roman sculptors we study presumably worked with live models just as modern artists do. How is it similar or different to use a statue as opposed to a living person as a model? What kinds of connections do you see between your life studies and your paintings of statues?

WA: When painting statues, I like to see the person within, the model who posed. The same kind of switch that occurs when a painting snaps out of being marks on paper and into three-dimensional illusion can happen when you look at statues and allow them to come to life. The light moving over the surface of the stone softens, the faces fill with expression or gaze ahead with compelling blankness. Similarly, I often see the live models as statues and paint them as such. The utter immobility of statues is a double-edged sword: the luxury of having limitless time can lead to an overworked painting, particularly a watercolor, which cannot be changed or erased. On the other hand, it is quite easy to start anew with a statue, to recreate identical light and angle and try again. Painting live models is the opposite: they move, breathe, and often cannot hold a pose for long. They are also expressive, surprising, inspiring, and alive. Symbolically, the statues represent eternal life, while painting models is a way of stopping time, of capturing the way a shadow falls, a memory, or youth. Painting the models helps to keep the paintings of statues alive and light.

When I was at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, I was working with models who had become union workers during the revolts of 1968, which meant that they had been posing for 20 years. Each one had a repertoire of a few standard poses, and thousands of drawings were made of the same model in the same pose from slightly varying angles. This was excellent training for seeing beauty in the overlooked, the ordinary, for focusing on the light, the atmosphere, “mark-making.”

Now, when I work with models, I almost never give them instructions. The only indication they have is the duration of the pose, from 30 seconds, to 5 and 10 minutes, to half an hour. This way the models enter into their own reality, and their poses are natural, imaginative, and expressive. One of my models used to reenact the poses she had seen on billboards while coming to my studio. Another became the animals of the theatrical piece she was performing. Yet another asked, at the end of the session, whether anyone had guessed what he was doing. He had taken the poses of the 12 Stations of the Cross.

Other models take inspiration from old life drawings or classical statues. I often do not manage to guess, nor does it occur to me to guess, what sources of inspiration my models are drawing upon; my inspiration is their presence before me—somewhat like the statues, made at a different era for a different purpose. The poses and the quality of the painting do not necessarily go hand in hand. It is possible for the models to take a really fantastic pose and for the painting not to go well, for whatever reason, since it is all fairly hit-or-miss. It is also possible, however, to do a really great picture of a really boring pose. But the best possible situation is when the models take a fantastic pose and I am able to capture it; then it sometimes feels like magic, as though the painting is just creating itself—very exciting.

The Ideal

CR: One of the “disciplines” of your work—and your medium—seems to be to paint what you see without changing the basic contours or proportions of your subjects. That is why, if I understand correctly, you do not alter the faces of your live models so as to make them more “beautiful” or more regular. Indeed, it is interesting to me that you frequently leave the faces of your models blank. With statues, it is as if the work of translating individual faces into something more generic or “ideal” has already been done, so that when you paint a statue, you can both paint what you see and paint an “idealized” figure. As I think you once told me, that is one of the reasons why you paint statues. Now I have put the words “ideal” and “idealized” in quotation marks because many historians of ancient art are very wary of those terms; we are generally wary of the notion of “universal ideals,” and specifically wary of a tendency to idealize ancient Greek and Roman civilization. The Greeks of the 6th and 5th centuries BC, for example, were certainly interested in beauty, but their ideas of beauty were in many ways socially determined, just as modern ideas of beauty are in many ways determined by the fashion industry. What does the word “ideal” mean to you? Why do you want to paint “idealized” images of men and women?

WA: I think that my models might be offended if I were to stylize and idealize their faces! The mere idea reminds me of those statues whose ancient bodies were restored with newly made stylized manneristic heads, restorations that are now themselves historical and thus unchangeable.

I wonder, can a portrait ever be universal? Can one look at an interesting face and not wonder about the specificity of the subject, about his or her life, and about how that person came to be painted? In general, I have not wanted my nudes to be anchored to an individual: although I personally know who the model is, I do not want the paintings to be portraits. I want them to be universal, for the viewer to be able to connect to his or her own body through my paintings of bodies. I feel that I am sharing my vision with the viewer, a vision that is in the language of the body, wordless, physical and present. With a nonspecific model, the painting is of one person who represents all people—you, me, our friends, family, or lovers. It is about the white shapes of paper that blend into puddles of watercolor, about how a pivoted torso feels, or about a pensive stance. It is about the selection that happens naturally in the making of a picture, an additive process, where one begins with a blank page and only puts in what one wants to paint—neither blurring nor obscuring, as one would have to do with a photograph—simply choosing to keep things as they are, suggestions, evocations, without adding detail.

I have always derived pleasure from beauty. Perhaps for this reason I have been drawn to the “ideal” in classical sculpture, and the idea of a shared canon of beauty. The “classical” human ideal often involves simplification and regularization: a straight nose, full lips, a muscular rather than lumpy or bony physique. Some of these attributes reflect health, fertility, desirability. Pushed to an extreme, these simplifications or stylizations can end up cartoony; the other extreme would be a plaster cast of an actual human body, hard to read, irregular, complex, and highly personal. Ancient statues have a subtle combination of naturalism and simplification. The “ideal” is to me the human desire to strive for excellence, the projection of a higher standard. These standards are often very much based on what is familiar to us, on what surrounds us, so that we develop an appreciation for the whiteness of classical statues although they were often originally painted, for the stains and chips running along their previously unblemished surfaces, for the thick female statue torsos that are so unlike the canons of contemporary beauty.

So to answer your question: in fact I never try to duplicate the statue or nude that I see exactly: I am always trying to capture the ideal, the essence that makes a figure special and beautiful, so that my work will communicate universally. This is why at times I try to see through the statue to its source of inspiration.

The Parthenon Frieze

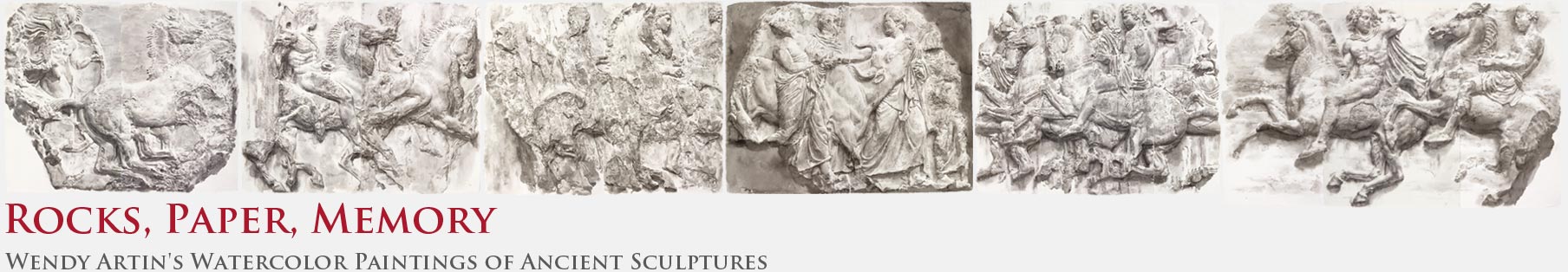

CR: When I first saw your paintings of the Parthenon frieze, I liked them immediately. I found them really captivating. I think what I liked about them first was what I liked about the Parthenon frieze itself (or rather, what I liked about the photographs of the frieze that I came to know and love, long before I ever saw the sculptures themselves), namely, the subject: a procession of men and women of all ages come together on some great occasion of which the central feature is a parade of young horsemen who project an extraordinary sense of inner discipline, in part because they seem to manage their unruly horses so effortlessly. There is a beautiful informality to it, so that it is serious without being solemn, grand without being grandiose. Earlier on, you commented on the “compelling blankness” of some ancient faces, and that is a great way of describing the expressions of the figures on the Parthenon frieze. It is that blankness that makes them seem so calm and self-controlled.

Here’s a comparison: on important occasions in western Turkey, men perform a traditional folk dance called the Zeybek, famous for its elaborate footwork and its stately pirouettes. But the parts of the Zeybek I find most elegant are the moments in between the formal steps, when the dancers simply walk around in a circle, bodies loose, heads down in concentration, moving casually but purposefully to the music… the Parthenon frieze projects something of the same mood and rhythm, and I think you have captured that in your paintings.

Now as I learned more about Greek sculpture and finally traveled to London to the see the frieze for myself in the British Museum, I began to appreciate other aspects of the monument, the intricate composition of its densely packed and overlapping figures, the extraordinary craftsmanship, the materiality of the stone. In the same way, as I have studied your paintings, I realize that part of what appeals to me in them is the texture of the paper, the tonality of the pigment, and the fascination of the way you use the play of light and shadow to give volume to the figures that you paint.

So those are some of my reactions to your paintings: what drew you to this subject? What are you trying to achieve by painting the Parthenon frieze?

WA: When I first saw the Parthenon frieze at the British Museum, I was dazzled by the rhythmic movement of the immortal horses and riders, by the long, delicate, powerful parade of stone.

The frieze bears eloquent witness both to the finesse of its designers and carvers and to the ravages of time; its figures literally embody the dialogue between time and civilization. Drawing something is a way of being with it for a long time, staring at it for a long time. For years, I dreamed of painting the frieze, of spending hours getting lost in the cracks and relief, understanding the movement of the heads, the bodies, the legs. I was not able to move my family to London but instead decided to make pictures at a scale that I could not possibly have done in situ, using photos. The frieze has a solid band of horse and rider bodies running through the middle of the frame. The heads are visible at intervals above the bodymass, the horses with almost wild expressions in contrast to the grave, impassive gazes of the horsemen. The legs form rhythmic patterns below, musical, counterpointed in the delicate manes and the fluted folds of the drapery. There is a surprising combination of movement and utter stillness.

Painting them I discovered that the cracks and fragmented rock were almost as visually compelling and certainly as demanding to represent as the sculpture itself. In one of the paintings, only one face remains, the rest being just craggy rock, suggesting the ghost of what was once there. As I painted, I found myself wondering about how much I was paying tribute to the bravura of the ancient and extraordinarily skilled sculptors and how much to the hand of time.

I wanted the image to emerge from the paper with no discernible start or finish, as happens in the process of drawing. I tried to capture all of the gradations of tone within one wet wash, before the brushstroke dried, pushing a dark in here and lifting light out there, in order to keep the watercolor fresh, light, on the surface. The organic surface and irregular absorption of the handmade rag paper that I use lends itself to the depiction of the stains of age, the crumbling of rock. I wanted the illusion to be almost total, for the realism to pull the viewer in at the same time that the brushstrokes remind one that this is simply wet pigment that has stained the fibers of the paper. By the end of the project, walking into my studio with the seven life-sized Parthenon frieze paintings felt a little like walking into the Duveen Gallery of the British Museum.

Technique

CR: When you first started making paintings of ancient sculptures, you focused on figures in the round; your series on the Parthenon frieze is part of a new project, it seems to me, to paint reliefs as well as freestanding statues. Reliefs are of course inherently more pictorial—they have a frame; they cannot be seen from behind—and in this way they are reminiscent of your paintings of urban walls, just as the paintings of statues are reminiscent of your figure studies. I am interested in how the two different kinds of subjects interact for you, and on that note, I would like to ask a technical question about your methods for making paintings of ancient sculptures. I know that you used photographs in your paintings of the Parthenon frieze. Did you also make sketches of the sculptures in the British Museum? For the freestanding statues, do you also sometimes use photographs?

WA: Freestanding or frieze, given the choice, I always prefer to work from the actual object, as the visual impact of and wealth of information in the subject itself is far more inspiring to me than even the finest photograph. Particularly when working at a large scale, this is frequently not possible. I find that the best method is to do a smallish picture on site—for composition, tonal impact, and emphasis. Sometimes there is not enough time, the angle is not attainable, or the scale or medium in which I am working is impractical in situ, in which case I am happy to be able to use photographs for reference. When working at a large scale, I always grid off the photograph in order to avoid glaring proportional mistakes. I draw the grid directly onto the photograph, but on my watercolor paper I indicate only the intersections with pale watercolor lines. I work outwards from one area rather than working a little bit everywhere. I often start with the face since, if the face does not come out well, I need to start over.

CR: Here’s a more specific question about technique: your paintings of the Parthenon frieze are astoundingly faithful to their subject; but since you were painting on sheets of paper instead of a roll, there are seams between the paper that resemble but do not correspond to the joints between the blocks that make up the frieze. If I were a critic, I would say that you are asserting the autonomy of your medium here. Would you agree with that?

WA: My favorite paper for large watercolors is handmade cotton rag paper made in India, pressed between layers of woolen felt, dried on lush green hillsides in the Himalayas. This paper does not come in widths greater than 70 centimeters, and the Parthenon frieze blocks are sometimes twice that. In order to make the pictures of the Parthenon frieze at actual size, I needed to either change paper or to piece together my favorite paper. I decided to piece the paper together, and in some cases the face was in the middle of the block. Since I did not want to have a seam running down the center of the face, in those cases I used three pieces of paper. Had the paper been available in a larger size, I would have used just one sheet, yet the abutting edges do not bother me at all.

Stone from Delphi

CR: The relationship between word and image has long been a subject of both artistic practice, as in medieval illuminated manuscripts, and art-historical analysis; there is even a scholarly journal explicitly called Word and Image. Your work for Stone from Delphi was the first time, I believe, that you created a series of paintings specifically designed to be paired with texts. Is that the kind of project you would enjoy repeating?

WA: Stone from Delphi was a wonderful experience. It was an honor for me to be chosen to make the pictures to accompany the classically themed poems by Seamus Heaney and a great challenge to make pictures that would stand in relation to the words and complement the experience of the poetry. I did not seek to translate the poetry into images: my sources were the statues of antiquity, whose sources were the myths themselves. Reading Heaney’s poems opened up new perspectives on classical statues I had painted all my life. Researching the mythological characters Heaney evoked, I discovered many other statues to paint pictures of as well. I would be happy to do another project of this sort.

Aphrodite

CR: Let’s talk about Aphrodite. The figure type represented by the statuette from Rhodes that you used to illustrate one of Heaney’s poems is known as the Aphrodite Anadyomene—Aphrodite Rising from the Sea. The conventional interpretation of her gesture is that, having just emerged from the sea from which she was born, she is wringing the water out of her hair. You pointed out to me that this is not the way most people would do that (they would gather their hair into a single skein and use both hands to wring it out, like a towel). What do you think she is doing?

WA: There are other images of Aphrodite Anadyomene where she appears more convincingly to be wringing out her hair. Here, unless she is planning to sit with her arms up in an uncomfortable position until her hair air-dries, it looks unlikely that that is what she is doing. For a painter, she is gracefully occupying a nicely rectangular shape of space, which eliminates the typical repetitive triangle made by the head and shoulders. But being a classical statue, it is unlikely that the sculptor simply asked her to stay in that fairly odd pose… To me, she looks like she is somewhat demurely displaying or making an offering of her hair.

Jupiter

CR: I wondered if you could talk about the process by which you chose the images and made the paintings for Stone from Delphi. To an art historian, it is striking that you represent Jupiter with the figure that we know to be an image of Laocöon—the Trojan priest who warned his countrymen against the Trojan horse and was devoured by serpents as a result. Perhaps you could speak to that…

WA: Images, poses, themes: these have been sources of inspiration, transformed and reborn, again and again over time. For the publication of Stone from Delphi, although I was offered the possibility of making etchings or another kind of print, I decided to do what I could do best: paint watercolors of classical statues. To go with the tradition of letter-press printing, these needed to be painted the size of the image that would appear in the finished book.

For the Jupiter in Seamus Heaney’s poem referring to 9/11, “Anything Can Happen,” I did at first look for a classical statue of Jupiter. But all those that I remembered or found showed a stately and dignified Jupiter, without the emotion and grief of Laocöon that is so appropriate for the poem. I had never previously painted Laocöon, and for the Stone from Delphi project I did first a small sketch, then the large picture that is in this exhibition, and finally the painting that appears in the book. The use and reuse of poses, faces, and themes is an ancient artistic practice, as in Masaccio’s fresco of Eve in the pose of the Aphrodite of Knidos and countless others.

Actaeon

Another time that I used a different subject is the statue from Herculaneum that I chose to accompany Heaney’s Actaeon. Although it is identified in academic literature as a deer who has caught his antlers in brambles, it looks to me like Actaeon being attacked by his hounds. It is a very interesting sculpture since it so perfectly illustrates the contrast that I frequently find in ancient statues between grisly themes and representational delicacy and finesse.

Inspiration

CR: Your paintings clearly engage, in one way or another, in a dialogue with the past. Classicists use different words to talk about these kinds of dialogues, such as “reception,” a catch-all term that refers to any kind of engagement with earlier traditions, from Raphael’s School of Athens to Heaney’s “Actaeon” to the kinds of academic practices embodied by departments of classical studies and museums of archaeology. In the most general sense, reception subsumes all the ways we comprehend the past, in art and literature as well as scholarship. The term I have chosen for the title of your exhibition is “Memory,” which I use to refer to the active process by which people establish and renew their links with the past, for example, through visits to “memorials,” or to sacred places, or, once again, to museums. You told me in an earlier conversation that you draw “inspiration” from ancient sculptures. What is it that inspires you, and why do you turn to the past?

WA: When I was a child, my parents often brought me to museums, and drawing the statues was a way of keeping myself entertained. Later, during art school and beyond, I continued to seek refuge and concentration in the stillness of museums. Painting statues “en plein air” was a way of painting my favorite subject matter, people, while also being outdoors. As time went by, I simply grew more and more curious about the statues, eventually developing thematic projects. Painting statues has been a bit like living in a foreign country or learning to use watercolors: at first you arrive and see the superficial, then bit by bit, with immersion, you become more and more interested, refined, curious, enamored.

Sitting in the stillness of a museum and drawing is a long, slow and tactile process, while everyone else ducks in and out, takes a snapshot. My pictures are nostalgic: I am trying to evoke the statue, and also all of the emotions and responses that the statue itself evokes. Painting is a way of slowing down and taking possession while creating the thin transportable expression of one’s vision, which is the drawing. It is magical to watch the image emerge from the materials, to see the illusion start to happen. It is always thrilling to watch other people draw and paint too, to watch the image emerge, to see how they are seeing. I love when classes paint from my paintings, and when people tell me that they saw something that I would want to paint, because this means that they have come to see it through my eyes.

I paint pictures of ancient statues because I find them beautiful. They have a level of simplification of the human form that is neither too polished, smoothed, or rounded nor too ruggedly naturalistic. They are an exquisitely harmonious blend of naturalism and stylization, abstracted by the erosion of time. The statues are for me both familiar and universal: as close to you as they are to me, as intimate for you as they are to me.

Emulation

CR: I want to return to the subject of the “discipline” of your work, namely, its fidelity to its subject matter. And I want to make a connection with the Roman practice of “copying” famous Greek statues. This was a fascinating cultural habit, and it is still a major focus of current scholarship. For a long time, much of this scholarship consisted of “mining” the Roman “copies” for evidence for the Greek “originals” that stand behind them, with very little attention paid to their status as objects made for specific contexts and specific users in the Roman period. An alternative school of thought, represented here at Michigan by my colleague Elaine Gazda, draws attention to the facts that these “copies” were usually made in materials different from the “originals” (marble rather than bronze) and that they regularly differ from each other in ways that seem to reflect deliberate choice. Starting from these premises, Elaine and like-minded scholars proceed to try to recapture Roman “copies” of famous Greek statues for the history of Roman art, showing that they are not mechanical reproductions but creative variations on ancient themes that tell us a great deal not only about Greek art but also about Roman society. Central to their argument is the Roman practice of aemulatio, usually rendered in English as “emulation.”

Opponents of this view have argued that fidelity to the model was of the essence of this kind of Roman sculptural practice. Rather than having regarded a “copy” as something inherently inferior to an “original,” Roman sculptors would have gloried in their ability to portray their models with extraordinary fidelity, even when working at different scales or in different media—and Roman viewers would have prized and admired such displays of artistic virtuosity.

I guess I’ll leave my short disquisition on Roman copies of Greek statues at that and simply pose to you the very open-ended question: do you think this has any relevance to your work?

WA: I am not sure whether this has relevance to my work. In art as in music, I relish repetition. I love stripes and trills, choruses and variations. I suspect that this love for repetition extends through my entire life: eating many artichokes, running the same favorite route, seeing the same beloved faces. We repeat in order to learn, in order to play music together, in order to become manually dexterous, in order to relive enjoyment. Painting from life in any form is on some level copying, or repeating, since the image is before you. Then it becomes a question of degree, how faithful one is trying to be, or how independent. Does one try to duplicate the original exactly, whether it is a person, a statue, or a photo of a statue? Or is it simply a point of departure, a grain of inspiration, a muse?

How close were the original ancient Greek statues to their models? I think that many of the ancient statues were in bronze, which means that they were in a sense already copies of the wax models through which they were created. What I have for statue-models, then, is the plaster or marble statue copy of the bronze copy of the wax copy of the live model and the imagined ideal of the original sculptor. This chain of metamorphoses is somewhat reminiscent of the children’s game Telephone, where the message passes from person to person, modified each time.

Although I cannot know what the ancient Romans were trying to do, whether it was exact replication of the Greek statues in a different material or some kind of artistic interpretation, I know that a fundamental aspect of my paintings of statues is the creation of a two-dimensional image, the lightness of a watercolor painting, and the relative abstraction of the statue. Like seawater lapping at the edge of the beach, if the sea is total illusion and the sand is blank paper, I like to be right at the water’s edge, between illusion and materiality.

Realism

CR: One of the distinctive characteristics of your work as I understand it is its “realism.” Your paintings are so faithful to their models that I could and indeed have used them to illustrate my classes on ancient sculpture, and in this way they recall the engravings used to illustrate paintings and sculptures in art-historical writing before the advent of photography.

WA: I am glad that you show my work to your students in order to show what the original statues look like. To me, that means that the details that I considered most important actually evoked the statue for you too. But if you look at my paintings, they are very obviously made of brushstrokes and washes. For them to be successful for me, they need to be loose enough to show the medium to its advantage and precise enough to create an illusion of reality.

To return to your earlier question, and the issue of reproduction, I find what I know of Elaine Gazda’s ideas on the ancient sculptors very interesting: in particular, that there were sculptors with specific specialities: this one sculpts the most beautiful arms, so if you want to have a beautiful arm, emulate his arms; this one sculpts the most beautiful faces, so if you want to have a beautiful face, make it like his. The idea being that then if all individual best pieces were put together, the result would be a very sublime sculpture. I love the idea that there were ideal faces, ideal arms, and a general consensus on those ideals.

By the way, it is so strange to me that they were polychrome. The white of the marble has always seemed like the white of the paper for me.

Ancient Artists

CR: One of the collaborations I most enjoy in archaeology is working with architects—partly because their technical skills are so useful, and partly because they are usually just better at imagining things in three dimensions than archaeologists, but also because they often seem to feel a direct connection with ancient builders. I think I tend to see the architectural puzzles we have to solve in archaeology—Where did this block go? Is this feature original to the construction of the building or an addition?—in a fashion analogous to that of a scientist trying to explain natural phenomena. My architectural colleagues, on the other hand, see them in human terms—What were they thinking? Why did they do it this way?

Art historians also have a difficult time understanding the motivations of ancient artists. We expend a lot of effort trying to reconstruct the “artistic personalities” of the relatively few ancient painters and sculptors and architects known to us by name—Apelles, Praxiteles, Ictinus—but for the vast majority of “anonymous” ancient artifacts, we fall back on formal or stylistic or technical analysis and on social and cultural interpretation, without giving much thought to the minds of the craftsmen who spent hours or days or months or years laboring over the objects we study.

When I was discussing your work with a student here at Michigan, she wondered whether you ever reflect on the artists who created the sculptures you paint. Do you feel a connection with them? When you make a painting of a statue, do you think about the mind behind the object or just about the object itself? How can contemporary artists help us understand ancient art better?

WA: My approach is purely aesthetic: I do not know who, why, or when the statues were made. I walk around and visualize paintings I would like to make, and I can only make a fraction of them. What I do make is never what I intended because the making is so exciting that I end up being caught up in how the pigments run across the paper, then look and decide to leave this, increase that, and suddenly the process of painting has overtaken the initial idea. Like finding out about the composer of a beautiful piece of music; answers to who, why, when, and where the statue was created come afterwards, and add great interest—once the painting is finished.

Roman Landscapes

CR: We have talked about your paintings of ancient statues and your figure studies, but not about your landscapes. Here too you are engaging with the past, and very directly with, to quote the title of a book I loved as a child, the “pleasure of ruins.” You are also taking your place in a grand tradition, both low and high, of making vedute di Roma. Where do you see yourself in that tradition?

WA: Rome is so beautiful. I had never been interested in painting landscapes until I arrived in Rome, and then set myself the goal of painting one landscape per day. I started out with simple silhouetted images of domes and pines. Bit by bit I allowed the backlighting to slide to the side, which you can see in my painting of the columns of the Temple of Saturn. Sometimes I tried to imagine how a painting of the landscape before me would look if I saw it and wished I had made it, and then I would try to paint that image. As I continued, the paintings became more and more complicated, until I was relishing the most complicated views, the visual mayhem of ancient ruins, baroque domes, and trees. I learned how to measure and grew to love the repetition of arches, of windows, of columns. I was able to sit outdoors for weeks, months, years. The weather is good for “plein air” painting in Rome. Some days I see my subjects just as piles of stones, but I started the paintings when I thought I was going to leave Rome forever, as nostalgic treasures.

These pictures are a very contemporary look at the remains of the past: I am not painting the buildings of the Romans but the vestiges of those buildings, as when I paint the remnants of chipped statues or the plaster copy of an artifact. The subject matter is rich with history and romance, the ruins poignant remains of what is no longer there. Time and erosion have turned the man-made into interesting organic forms. I use sepia watercolor to capture the warmth and brilliance of the Roman sunlight.

A couple of years ago I was speaking with the poet Jessica Fisher at the American Academy in Rome, who said that she wanted to write about Rome but that so many people had written about Rome, she did not simply want to fall into their well-worn tracks. People have already written about the parasol pines, the ruins, she said.

I said, what about nostalgia? Revisiting what you love, over and over again. There can never be enough pictures of the loved one: originality is not the point. Each new image is another moment of reliving that beautiful thing that is not present. The pictures, or poems, are like the key that you take away with you instead of all of your weighty possessions.