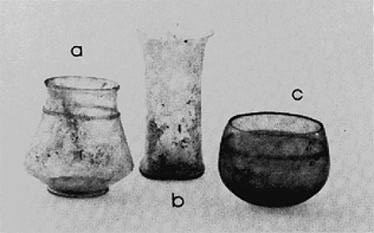

Moving from the sublime to the mundane, we come upon hoards of glass which

suggest a more cavalier attitude toward the glorious medium. Something like the

modern custard dish that is usurped for paper clip storage is the rather

dignified beaker which was found inelegantly

stuffed with a crumpled wad of linen and two bone pins. The family

inhabiting house B 121 at Karanis evidently had a distinct penchant for

innovative uses of their glass containers. In the same hoard together with the

beaker was found a

Moving from the sublime to the mundane, we come upon hoards of glass which

suggest a more cavalier attitude toward the glorious medium. Something like the

modern custard dish that is usurped for paper clip storage is the rather

dignified beaker which was found inelegantly

stuffed with a crumpled wad of linen and two bone pins. The family

inhabiting house B 121 at Karanis evidently had a distinct penchant for

innovative uses of their glass containers. In the same hoard together with the

beaker was found a

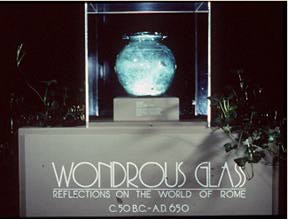

ROMAN GLASS-MAKING

The Background

Glass is formed when sand (silica), soda (alkali), and lime are fused at high temperatures. The color of the glass can be altered by adjusting the atmosphere in the furnace and by adding specific metal oxides to the glass "batch" (such as cobalt for dark blue, tin for opaque white, antimony and manganese for colorless glass). A venerable legend perpetuated as late as the seventh century A.D. in the writings of Isidore of Seville gives a suitable miraculous explanation for the discovery of this elemental--yet truly wondrous--material:This was its origin: in a part of Syria which is called Phoenicia, there is a swamp close to Judaea, around the base of Mt. Carmel, from which the Bellus River arises . . . whose sands are purified from contamination by the torrent's flow. The story is that here a ship of natron [sodium carbonate] merchants had been shipwrecked; when they were scattered about on the shore preparing food and no stones were at hand for propping up their pots, they brought lumps of natron from the ship. The sand of the shore became mixed with the burning natron and translucent streams of a new liquid flowed forth: and this was the origin of glass.It is not surprising that the ancient authorities thought of Phoenicia as the birthplace of glass, for the Syro-Palestine region did indeed become a major center of glass production in antiquity, along with Egypt. However, glass seems actually to have been "discovered" not in Phoenicia, but in Mesopotamia. Archaeological research now places the first evidence of true glass there at around 2500 B.C. At first it was used for beads, seals, and architectural decoration. Some 1,000 years elapsed before glass vessels are known to have been produced. Vessels of glass quickly became widespread in the second half of the second millennium B.C. They were popular not only in Mesopotamia but also in Egypt and the Aegean. The earliest vessels were core-formed. Opaque, dark glass in its molten state was wound around a clay core attached to a metal rod. The skin of hot glass was fashioned with tools in order to shape its external features. Lighter colored strands of hot glass were then trailed on the surface and often "dragged" to produce festoon patterns. The pot surface was marvered (that is, rolled on a smooth, flat surface to produce a level finish). Finally, it was cooled slowly before the clay core was scraped out of the hardened vessel. his glassware typically imitated forms originally established for ceramic, metal, and stone vessels .

Somewhat later, the molding technique was developed, whereby glass chips or molten glass were packed or forced into a mold and then fused. After a molded vessel was annealed (cooled slowly in a special chamber of the glass furnace), it was often fround and polished in order to refine the rim and any other rough edges. One typical shape for molded vessels of the late Hellenistic and early Roman periods (c. 150-50 B.C.) was the so-called pillar-molded bowl(NEED PHOTO FOR THIS). Here exterior ribs radiate up from the base, stopping abruptly near the rim to allow a smooth margin around the circumference. This type is ubiquitous; and it attests to the free and rapid exchange of ideas in glass-making throughout the Greater Mediterranean sphere. Fragmentary examples in the collections of the Kelsey Museum range from Seleucia, to Karanis, to Puteoli (II: 7 a,c,d). The site of Tel Anafa in Israel (recently excavated jointly by the Universities of Michigan and Missouri) has provided critical information on the chronological limits of these bowls within the Roman period (II:7b).

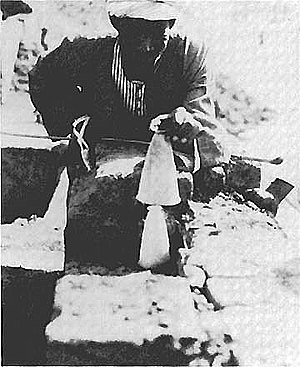

Around 50 B.C. a revolutionary development occurred in the history of glass-making: the invention of free-blowing. This landmark achievement did almost certainly take place in Syro-Palestine even if the basic discovery of glass did not. Perhaps the significance attached to the Syro-Palestine glasshouses because of the discovery there of the blowing technique is at the root of the ancients' tendency to attribute to Phoenicia the invention of the actual material as well.

The free-blowing process required a continuously fired furnace. A wad of molten glass was gathered on the end of a long metal pipe. By blowing air through this pipe, the molten "gather" became a bubble of glass that could be manipulated with tools and reheated periodically for easier working. After the application of elements such as base-pedestals, a metal rod ("pontil rod") was thrust onto the bottom of the vessel and the top was cracked off the blow-pipe. Then, with further reheating, the top of the vessel received its final shaping; and elements such as handles and decorative trails were applied from a molten gather (Fig. 1). Vessels produced in this way often preserve a scar, or "pontil mark," on the base from the removal of the pontil rod. When complete, the vessel was placed in the annealing chamber of the furnace.

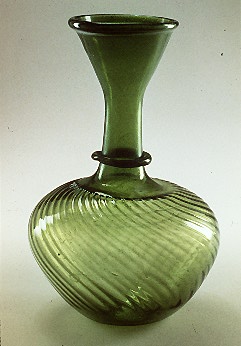

With the development of free-blowing, the rather staid uniformity and refinement of cast vessels often gave way to directives of speed, spontaneity, and formal ingenuity. Less architectural in profile, blown vessels of antiquity often achieved a graceful, thin-walled elegance (Pl. 5) or a loose, plastically volumetric vigor (Cover illustration). Depending upon the quality of the raw glass, the finished product might yield a bubbled, grainy texture or a compact and pure one. The iridescence seen on much ancient glass was not a deliberate effect created by the glass-maker. It was caused by devitrification (chemical decomposition) due primarily to prolonged contact of the objects with moist and acidic soil in their archaeological contexts. Paradoxically, vessels displaying this opaline quality are coveted by many collectors of antiquities because of their aesthetic appeal; and the effect is frequently imitated by modern glass-artists. Since the majority of glass and artifacts in the collections of the Kelsey Museum come from Egypt, with its dry climate, relatively few of them illustrate this phenomenon. They appear for the most part as they were intended to look some 1500 years ago.

Glass of the Roman Empire

The invention of glass-blowing occurred within an historically critical span of time. In the middle years of the first century B.C., the power of Rome was fanning out to embrace East and West in a military/political hegemony that would provide the substructure for expansive trade networks and patterns of cultural exchange. The blossoming of this internationalism is mirrored in the glass industry of the Roman Empire. Rome asserted its control over the two dominant glass-making centers of the late first millennium (Syro-Palestine and Egypt) in 62 and 30 B.C., respectively. Simultaneously, the raw territories of the West (where glass had no history) were being brought within the orb.It is telling that the earliest known ancient representation of glass-blowing has been found not on an object from Phoenicia, but on an object from Split, Yugoslavia: a decorated clay lamp datable to the first century B.C.; and, while Syro-Palestine and Egypt maintained their traditional importance as glass-making centers, glasshouses were already in operation in Cologne, Germany (to offer one example) by the middle of the first century B.C. Cologne rapidly developed a major industry which was continuously responsive to trends set further east, while also responsive to local predilections. Until well into the fifth centry A.D., when effects of the political dissolution of Empire began to be reflected perceptibly on the level of material culture, there was a remarkable unity in glass-making across the entire extent of Rome's purview. Not only did glass products travel (both as objects of intrinsic trade value and as receptacles for liquid commodities [Pls. 9 and 10]), but so also did glass-makers. This is clear from a variety of textual, epigraphical, and artifactual evidence.

Pl. 9. Ungentaria and a flat-bottomed bottle flask

(a) XII:3; (b)XII:4;

(c)XII:11; (d)XII:8;

(e)XII:2; (f)XII:10; (g)XII:1

Pl. 10. Shipping

jugs (a)X:6; (b)X:5

Within a few hundred years from the invention of free-blowing, glass-blowers had developed almost all the major decorative techniques which are used by glass artists even to the present day. Thus, in essence, the glass of the Roman Empre provides a telescoped view of the techniques of art in glass generally, from antiquity until the emergence of the studio movement in our own era. The one major exception was the concept of stained glass windows, not envisioned until the Middle Ages.

Decorative Techniques of Roman Glass

When a glass vessel is being blown, and thus is still in its heated state, its surface form as well as its shape can be manipulated in many ways. In Roman times glassmakers took full advantage of the decorative potentials of their medium. A major by-product of the invention of blowing was the invention of mold-blowing. Here, a molten gather of glass was blown directly into a mold of two or more sides. Using this technique, thin-walled vessels with complex figural or geometric patterns (sometimes including inscriptions) could be created repeatedly and quickly (NEED PHOTO OF Pl. 11). The logo of the glass-maker Ennion frequently appears as part of the decorative scheme on his mold-blown vessels: "Ennion made me. Let the buyer remember him!" Through mold-blown inscriptions such as these we glimpse something of the glass-makers themselves. Regrettably, however, inscriptions of glass-makers on objects other than their products are very rare. For all the interest taken by Roman authors in the qualities of glass, allusions to the people who created it are few and far between. One curious story passed down from Pliny to Isidore of Seville describes the fate of a glass-maker at the court of Tiberius [A.D. 14-37]. The craftsman demonstrated to Caesar that he had invented a means of tempering glass so that it would not break when dropped but could be hammered back into shape like a bronze vessel. When the man admitted that he alone knew of this new treatment for glass, Tiberius had him beheaded "lest when this became known, gold would be valued like mud, and the values of all metals be debased." To what could this tale possible refer? It is tempting to postulate that it has something (however obscure) to do with the invention of mold-blowing. If not the actual inventor of mold-blowing, Ennion was certainly one of the very earliest masters of the technique. An Ennion-signed cup found at Corinth in Greece in a sealed deposit together with a coin of A.D. 37-41 now provides us with a firm date for the early range of his career. It dovetails nearly with the setting of this peculiar story in the reign of Tiberius.Pl. 11. (NEED PHOTO OF) A mold-blown bottle III:11

Pl. 12. Two-handled vessels (a)XV:5; (b)XV:1; (c)XV:10 (d)XV:2

Although free-blowing did not offer the advantages of mass-produced uniformity that mold-blowing allowed, the decorative potentials of the technique were seemingly limitless. While free-blowing a vessel, the glass-maker could achieve a variety of surface effects by drawing the glass out in thorn-like projections (Pl. 12b), by pinching it (Pl. 13c), by ribbing it or corrugating it (Pl. 6), or by indenting it at regular intervals (Pl. 24c and e). Once blown, a vessel could be decorated with thick or thin threads of molten glass trailed on the surface to produce simple coil accents, zigzag patterns, undulating "whisker" trails (Pl. 14a) or complex sculptural effects. Similarly, blobs of molten glass (usually dark blue) could be fused onto the vessel surface either in simple chains or in complex geometric arrangements (Pls. 5a and 24e and f). Decorative glass attachments of contrasting colors could be fused to the warm glass vessel also. These could be molded elements such as rosettes, lion-heads, theater masks, and the like (Pl. 16); or they could be free-blown attachments. Applied elements were often set at the base of the vessel's handle (Fig. 2). Sometimes they were used all over the vessel's surface, however (Fig. 3).

Pl. 13. Beakers (a)XIII:18; (b)XIII:1; (c)XIII:12

Pl. 14. Decanter and

wine glasses (a)IX:3; (b)IX:5; (c)IX:4; (d)IX:8; (e)IX:7; (f)IX:6

Table jugs

Pl. 16. A molded attachment III:22

Pl. 16. A molded attachment III:22

Once cooled, glass vessels could be decorated with cutting techniques performed with emery-fed wheels of different sizes. Essentially, these techniques exploited the structural similarities of annealed glass to compactly grained stone. Undoubtedly, there was a good deal of overlap between artisans who specialized in gem-carving and those who cut and engraved glass. This is no where more evident than in glass cameo work. Blanks for glass cameo vessels were made by casing dark (usually blue) glass with opaque white glass. When cooled, the exterior surface was cut back to produce figural compositions on multiple planes which exploited the shading variations made possible depending upon the degree of thickness or thinness of the reserved white. Cameo glass had an advantage over cameo carving in shell or stone in that the artisan could control the placement and relative depth of the contrasting materials in his blank. Cameo glass was a development emerging from the prosperity of the Pax Romana of the Augustan period in Rome (27 B.C. - A.D. 14). The technique seems not to have been practiced in ancient Italy after the first century A.D. Only thirteen complete cameo vessels are presently known worldwide. Preserved fragments number only in the hundreds (see IV:8,9,13-15). Dionysiac scenes seem to have been the favored subject matter for cameo vessels. Epic legends were also represented (as, on the famous Portland Vase in The British Museum an enigmatic mythological/epic tale unfolds). Suetonius tells us that the Emperor Nero (A.D. 54-68) "upset the table and dashed to the floor two favorite goblets which he called 'Homeric' after the Homeric tales carved upon them." These goblets were probably cameo-carved. The preciousness of cameo vessels is suggested by a still life painting from Herculaneum in which a cameo-carved jug bearing a scene with a horse and rider figures prominently (Frontispiece; for comparison, IV:15).

Mythological scenes were also engraved into colorless glass vessels. Alexandria produced a coveted class of this genre during the second century A.D. Fragmentary examples of this ware from Karanis prove that such glasses must have been made in Egypt, no doubt at Alexandria, for the inhabitants of provincial Karanis were not likely to import luxury items from Rome, Cologne, or Sidon. (See IV:16-18 and 24.) Completely preserved vessels of this type found in the West document complex captioned figural scenes. Vessels which were wheel-cut with elaborate designs of facets and grooves were also greatly prized. Some of these were executed on exquisitely thin glass (IV:19); while others embellish weighty vessels (IV:6).

In Egypt and the West during the fourth century A.D., a more shallow type of engraving was popular--with examples from Karanis (such as XI:4) paralleled impeccably as far away as Cologne. The most famous representatives of this technique are a series of eight flasks which depict around their bulbous bodies the topographical landscape of Puteoli, on the Bay of Naples. Of these eight, four were found in Italy, two in the Iberian Peninsula, one in North Africa, and one in Cologne. Apparently the bottles were all made at Puteoli -- where there was a flourishing glass industry. Four of the known vessels (including the Populonia Bottle, which is the only one of the group housed in a museum of the western hemisphere) preserve dedicatory inscriptions engraved just below the neck. These personal inscriptions were undoubtedly engraved at the time of purchase, requested specifically by the consumer. The scenes on the vases (with their labeling inscriptions) seem, on the other hand, to be stock types -- although no two are exactly alike.

Puteoli was an important commercial city -- a bustling port serving the Mediterranean traffic and also exporting a number of local products described by Pliny in his Natural History. Thus, one could well imagine businessmen and sailors purchasing vessels such as the Populonia Bottle and carrying them home as prized souvenirs. Four of the eight flasks include a representation of a temple and cult statue of the Egyptian god Serapis (a syncretistic deity who combined concepts of Zeus and Osiris and enjoyed vast popularity both in Egypt and in Italian port cities during Imperial Roman times). Conceivably, then, these four flasks at least were purchased more specifically as souvenirs of cultic pilgrimage to the famous Temple of Serapis at Puteoli which is well known to us from textual sources. The representations of Serapis on the glass flasks are quite similar to the image of the god as presented in a bronze statuette from Karanis which is thought to be a miniature version of the lost cult statue from the Temple of Serapis at that site (XVIII:B). Along with an eighteenth century engraving after an ancient wall painting of Puteoli (Photo Panel 17), the Populonia Bottle and its companion pieces have provided important documentation for archaeologists concerned with a study of the topography and social history of Pureoli. For our special exhibition the Kelsey Museum was especially pleased to feature the Populonia Bottle because we hold an important collection of Puteolian inscriptions and related artifacts which provide an intellectual backdrop for this rare vessel.

On the eastern frontier of Rome's active military purview, massive clear vessels embellished with deeply cut facets were a specialty.

Whole vessels of forms similar to our fragment excavated at Seleucia have been

found in Japan. One was buried with the Emperor Ankan in A.D. 535. Unlike the

devitrified examples found in the Middle East, the cut-glass vessels exported to

Japan are still in pristine condition--their facets dazzling like so many

mirrors. To date, no actual examples of such western ware have been

found in China; but on a painted silk banner from the Buddhist caves at Tun

Huang, a Boddhisatva holds one of these Partho-Sasanian faceted bowls so that

his hand is visible through the sparkling pale green glass. Thus, this striking

portrayal vividly documents the presence of western glass at a remote outpost

along the Central Asian Silk Route. Further evidence of the Chinese interest in

glass from the world of Rome comes in the form of lyrical poems composed by the

nobility in praise of such luxury vessels which had ". . . braved the perils

of the desert's limitless wastes, / And crossed the towering, precipitous

Pamirs" in order to grace their tables:

Whole vessels of forms similar to our fragment excavated at Seleucia have been

found in Japan. One was buried with the Emperor Ankan in A.D. 535. Unlike the

devitrified examples found in the Middle East, the cut-glass vessels exported to

Japan are still in pristine condition--their facets dazzling like so many

mirrors. To date, no actual examples of such western ware have been

found in China; but on a painted silk banner from the Buddhist caves at Tun

Huang, a Boddhisatva holds one of these Partho-Sasanian faceted bowls so that

his hand is visible through the sparkling pale green glass. Thus, this striking

portrayal vividly documents the presence of western glass at a remote outpost

along the Central Asian Silk Route. Further evidence of the Chinese interest in

glass from the world of Rome comes in the form of lyrical poems composed by the

nobility in praise of such luxury vessels which had ". . . braved the perils

of the desert's limitless wastes, / And crossed the towering, precipitous

Pamirs" in order to grace their tables:

Despite the vernal splendor of its hue,The tour de force of Roman glass-making was the diatretum technique, whereby a blank vessel was cut back to reveal a complex design connected only by narrow reserve struts to the remaining solid wall. One type of diatretum found almost exclusively in the Rhineland was the cage cup variety carved as a lace network around the exterior of the vessel (IV:11). Figural diatreta such as the famous Lycurgus Cup (Photo Panel 3) have a wider distribution. One, depicting the Lighthouse of Alexandria, was found in a hoard of treasures at Begram, near modern Kabul in Afghanistan. These figural diatreta are understandably rare. After Roman times, the technique of diatretum carving in either mode was not attempted again until the nineteenth century when deliberate imitations of the Roman cage cups were made in Bavaria. The extraordinary delicacy of the Roman diatretum vessels suggests the possibility that they were created on a special commission basis -- the glass-carver traveling with the blank vessel to the place where the commission originated. It is difficult to imagine how the Lighthouse diatretum could possible have arrived at Begram intact had it been carved before the arduous journey from Rome or Alexandria. So delicate and specialized was the carving process that a law was formulated to deal with the contingencies of liability for a faulty product, depending upon whether the blank vessel was inherently flawed or whether the glass-carver's ineptitude alone was responsible for a ruined effort (Text Panel 4).

Its clarity surpasses the purest winter ice.

There vessels are produced as though ceramic,

And their rare foreign shapes richly embellished.

Up to this point we have discussed decorative techniques of the Roman glass-maker which essentially exploit the potentials for textural variation. Nuances of color were, however, equally important qualities of glass--appreciated and exploited with finesse by glass-makers in the Roman period. One technique of great versatility in its applications was fused mosaic work or millefiori, which is an Italian word meaning "1000 flowers." Essentially this technique involves the fusing of colored strips of glass into a rod from which slices can be cut which will present on their sliced surfaces the section-pattern of the fused colors of the rod. These slices of patterned glass were used decoratively as inlays; and they were also fused into the glass matrices of beads and vessels to form overall patterns against a dark ground. Sometimes vessels and wall inlays were created using the millefiori method but placing the various colored and patterned elements in figural compositions (Pl. 18e). Elaborate landscape effects were achieved to the extent that it is sometimes difficult to remember that these designs were executed in fused glass rather than in paint. Interestingly, the vessel fragment V:31 (Pl. 18e) preserves a section of a mosaic glass landscape of birds among branches and flowers which is very reminiscent of a Dynastic Egyptian vignette of birds in an acacia tree seen, for instance, in the Middle Kingdom tomb painting of Khnemhotpe.

Pl. 18. Decorative inlays of glass (a)VI:19; (b)VII:17; (c)V:23; (d)V:24; (e)V:31; (f)VII:4

There were many variations on the concept of fused mosaic glass. Gold-band glass was a luxury ware in which gold leaf and swirls of colored glass were fused within a sandwich of colorless glass. Emerging out of the tradition was the technique of gold glass -- where figural representations in gold leaf were sandwiched in colorless glass. This method of decoration was used effectively in the late Roman period for the embellishment of cup tondos. These tondos (such as that on Photo Panel 4) have been preserved as detached elements because their owners broke them away from the surrounding cup walls in order to imbed them in the walls of the catacombs as funerary emblems. The appeal of the gold-glass tondos for this purpose lay in the fact that they were comissioned pieces, often including a representation of the owner and an inscription giving his or her name or a salutation. Many of these gold-glass tondos supply important material for the study of the iconography of Judaism and Christianity in the first half of the first millennium A.D.

In addition to the traditions of coloristic effects which relied on the fusion of variously colored glasses, the glass-makers of Roman times also developed the technique of enamel painting onto the surface of glass vessels. From Karanis, several fragments have been preserved which provide a sense of the range of colors used in enamel painting (V:25-26). A cup fragment from The Corning Museum of Glass demonstrates the dynamic effects possible with this technique (V:27). A lovely fragment of enamel painted glass in the Kelsey Museum (Pl. 19) displays an allover pattern of birds in hexagons. It is a late piece, dating from that interesting period of art in Egypt when Roman traditions were merging with nascent Islamic decorative modes. The mold-blown vessel fragment illustrated along with this piece demonstrates that the allover polygon pattern had already been established in the Roman period. Furthermore, the comparison suggests the easy interchangability of motifs from one decorative technique in glass to another.

Pl. 19. (a)A mold-blown vessel fragment V:29; (b)An enamel painted vessel fragment V:28

Special Uses for Glass

The coloristic potentials of glass determined its great popularity for special decorative uses. Fused mosaic glass of marble-like or figural patterns was employed, for instance, to adorn the surfaces of walls and furniture. When Pliny describes the Theater of Scaurus, built in 58 B.C. -- where the second story of the stage building was faced with glass -- he is probably alluding to mosaic glass made to imitate the swirling grains of marble (Natural History XXXV.24). Object VII:12 is an example of this type of architectural embellishment. At Karanis, an interesting variant of the marbling effect produced by means of the mosaic glass technique is documented by object VII:13. Here, a strip of colorless glass was laid over a base of stucco which had been painted to resemble marble. The practice of painting expanses of wall to imitate various marbles was a common one in Roman times (seen, for example, in the background of Pl. 28); but overlaying the painted glass zone with colorless glass, the Karanidian decorator achieved a richly reflective surface.Figural inlays of mosaic glass also decorated walls and furnishings. A striking piece from Karanis (Pl. 18f) preserves a small, exquisitely detailed theater mask set amid a profusion of flowers. This object is thick and tubular, with a longitudinal perforation too narrow to recommend the suggestion that it formed the neck of a long-necked flask. More likely it was a decorative furniture element. Mosaic glass in bold patterns seems to have been used throughout the Empire period to decorate walls. The fish and floral motifs seen on Pl. 18 have close parallels from Italy, while these examples come from Egypt. The fragment which preserves part of a scene of birds in a tree is, however, definitely from a vessel, the exterior of which was left in the severe black of the matrix glass and decorated only with two wheel-cut rings. A larger scale version of this same motif -- also in fused mosaic technique -- is housed in The Corning Museum of Glass. The mosaic glass panel in Corning was unquestionably used to face a wall. Thus, it effectively closes the gap between the traditional wall painting motif of birds in an acacia tree from Dynastic Egypt (mentioned earlier) and the appearance of a small-scale version on the interior of a fused mosaic glass vessel.

Colorful opaque inlays for opus sectile mosaic were found at Karanis (e.g., Pl. 18a). In this technique, the motifs were created from pre-formed shapes fitted together, such as the rosette shown here, with its central depression intended for a circular insert of contrasting color. Glass also came to be used in place of marble for tessera mosaics laid on floors, walls, and vaulted ceilings. The advantage of glass tesserae over marble one rested primarily with their consistently glittery quality and their range of colors, which could be produced on demand. According to Pliny, glass mosaic for walls and ceilings was introduced at Rome in the late first century B.C.

The myriad uses made of opaque and colorful glass notwithstanding, clear glass was the most frequently admired in the world of Rome. In Pliny's words:

. . . there is no other material nowadays that is more pliable or more adaptable, even to painting. However, the most highly valued glass is colorless and transparent. . . .Surely the single most remarkable quality of glass is its ability to contain objects and liquids and yet also to admit light and permit a view from within or without. Exploiting this property, glass was put to many special uses in Roman times -- ranging, as we might expect, from the ridiculoius to the sublime. Glazed windows became quite common during the first century A.D. Fragments of such glass found at Karanis (Vl:20-21) demonstrate that this early window glazing was rather thick by our standards. Although it let light in and kept wind and rain out, it was not transparent -- only translucent. Yet we can gain a sense of the healthy respect in which the ancients held their ability to create architectural enclosures that admitted light by reading Paul the Silentiary's rhapsodic description of Santa Sophia:

(Natural History XXXVI.66)

Thus rises on high the deep bosomed vault, borne above triple voids below; and through five-fold openings, pierced in its back, filled with thin plates of glass, comes the morning light scattering sparkling rays.The Romans made use of the quality of transparency for practical jokes as well as for truly practical purposes. The false-bottomed wine glass (VI:1) is a delightful example of the former. Here, the wine was poured through a hole in the base of the cup. After the wine had filled the entire space between the false bottom of the cup and the real bottom, the hole was plugged. Thus was achieved the appearance of a glass brim-full of wine. Another specialized use of glass at the banquet table is deplored by Seneca:

A mullet does not seem fresh enough unless it dies in the hands of the banqueter; they are passed around enclosed in glass jars, and their color is watched while they expire.To be sure, the transparency of glass opened up whole new worlds of observation. Most commonly it was a case of being on the outside looking in--as to observe the demise of the mullet. In one instance, however, we find glass being perceived as a useful medium in a situation where the person is on the inside looking out at the fish. The story of Alexander's exploration of the depths of the sea in a glass submarine, is of course, fabulous. Yet it has its roots in the fact that during the period when the legends of Alexander were developing, glass was coming into its own as a material of virtually unlimited versatility.

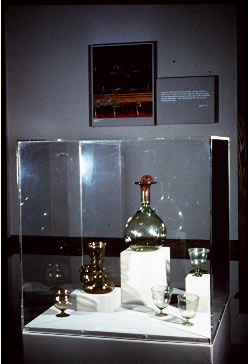

Practical and fanciful vessels of clear glass are illustrated by the spouted

"feeder" bottle and the two fragmentary bird-shaped perfume bottles

shown above. We take for granted the fact that it is a fine thing to be able to

see how much a child or an invalid is drinking, but how marvelous this ability

must have seemed in the early years of glass-blowing!

Practical and fanciful vessels of clear glass are illustrated by the spouted

"feeder" bottle and the two fragmentary bird-shaped perfume bottles

shown above. We take for granted the fact that it is a fine thing to be able to

see how much a child or an invalid is drinking, but how marvelous this ability

must have seemed in the early years of glass-blowing!

Dinnerware was sometimes made of glass (Pl. 21). It was especially good for summer banqueting, according to Propertius.

And drinking cups of glass came in every conceivable shape and size.

And drinking cups of glass came in every conceivable shape and size.

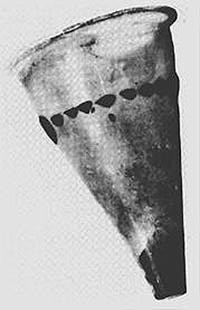

At Karanis, conical glass vessels were used both as drinking cups and,

apparently, as oil lamps to be held in fixtures for suspension (NEED PHOTO of

Pl. 24). In his study of the conical vessels from the site, D.B. Harden noted

that many were coated on the interior with an oily residue. He concluded that

they must have been the precursors of the conical glass oil lamps which are well

known from actual examples suspended from metal polycandelon fixtures in mosques

of the Islamic world. Chandeliers of this type are suggested in descriptions by

several Roman authors. The hanging lamps to be seen in Hagia Sophia today must

be very close to the sixth-century originals extolled by Paul the Silentiary:

At Karanis, conical glass vessels were used both as drinking cups and,

apparently, as oil lamps to be held in fixtures for suspension (NEED PHOTO of

Pl. 24). In his study of the conical vessels from the site, D.B. Harden noted

that many were coated on the interior with an oily residue. He concluded that

they must have been the precursors of the conical glass oil lamps which are well

known from actual examples suspended from metal polycandelon fixtures in mosques

of the Islamic world. Chandeliers of this type are suggested in descriptions by

several Roman authors. The hanging lamps to be seen in Hagia Sophia today must

be very close to the sixth-century originals extolled by Paul the Silentiary:

And beneath each chain he has caused to be fitted silver discs, hanging circle-wise in the air, round the space in the center of the church. Thus these discs, pendant from their lofty courses, form a coronet above the heads of men. They have been pierced too by the weapon of the skillful workman, in order that they may receive shafts of fire-wrought glass and hold light on high for men at night.

Wondrous Glass: Images and Allegories

The invention of glass-blowing occurred at a time when thinkers were pondering the physical phenomena around them. For Lucretius, the properties of matter were a primary concern -- not least the properties which enable us to see through glass but not through other materials. He writes:Though voice may pass unharmed through winding pores in things,Not long after these thoughts were formulated, glass became a favorite subject for still life painters eager to explore the qualities of transparence, color, and light. The earliest still life representations featuring glass vessels all depict the objects filled with fruit. As a motif, the still life with fruit goes back to Classical Greek prototypes known to us only through the descriptions of them by Roman authors. Pliny notes that Zeuxis "produced a picture of grapes so successfully that birds flew up to the stage-building". In any case, the thin-walled transparency of blown-glass vessels such as the carchesium from Toledo (Pl. 27) challenged the painter to capture the optical qualities of the glass container as well as the image of the fruit within.

yet images demure;

for these are rent asunder -- save it be they stream

Through passages unbent, as those of glass,

Wherethrough all atoms speed their winged flight.

Pl. 27. A carchesium VIII:1

Painters and poets were also intrigued at this time with the similarities between glass and water. Still life paintings from Herculaneum depict clear glass vessels filled with water. In these versions, the glass is transparent, and the water within is a glimmering surface of light. In a more lyrical way, the painting from Boscoreale also juxtaposes the qualities of glass and water. Here, the glass bowl of gruit, painted as if sitting on a window sill, is adjacent to an idyllic landscape scene in which shimmering-clear brook water trickles down over the rocks. Only a few years later, Horace was to compose his ode to the spring of Bandusia; and indeed, poem and painting evoke the same image of glass:

O spring of Bandusia, more shining than glass,The imagery associated with glass in the other poems by Horace is sometimes evocative of darker thoughts. "Indiscreet trust" is "as clear as glass and ready-charged with secrets to repeat" in Ode 18 of Book I; and Circe, in contrast to the faithful Penelope, is "like glass" in Ode 17 of Book I. So too, in the visual imagery of Roman art there is a darker side to the portrayal of one quality of glass, at any rate: Its quality of reflection. In every culture, mirrors are laden with associations of deep psycho-social significance. Rome was certainly no exception. A mirror could be any reflecting surface. In the Pompeiian wall paintings, imagery of reflection seems always to be of a foreboding kind: Narcissus with his face reflected in the dark pool of water; Thetis reflected pensively in the gleaming shield of Achilles; and the enigmatic scene of a woman in the Villa of the Mysteries whose image is reflected in a hand mirror. This last scene is puzzling on two counts. The image we are shown in the mirror is not the proper image that would be depicted if the painter's aim had been to show a rendition of actuality. Rather, we see a strange scene in which the standing companion looks down into the mirror; and in the mirror she sees the same view of the seated woman that we see from outside the picture. Furthermore, the form of the mirror is unusual, and perhaps unique. It must be either of silver or glass set into a folding, square "compact."

deserving of sweet wine and flowers,

tomorrow you will be presented with a kid whose forehead,

swelling with the tips of horns,

gives promise of both love and battles;

in vain: for he, the offspring of a playful flock,

shall stain for you your chill waters with his red blood.The black hour of the flaring Dog-Star knows

no means to touch you:

you provide pleasing coolness

for tired oxen and the straggling herd.You also shall become one of the famous fountains,

since I describe the oak tree planted over your hollowed rocks

from which your chattering waters jump down.

Pliny speaks of glass mirrors on several occasions. In one instance he is very explicit on the subject:

Silver mirrors have come to be preferred [to bronze ones]; they were first made by Pasiteles in the period of Pompey the Great [106-48 B.C.]. But it has recently come to be believed that a more reliable reflection is given by applying a layer of gold to the back of glass.By the seventh century, glass seems entirely to have usurped the place of metal for mirrors. At least, Isidore of Seville tells us that "no other material is more fitting for mirrors . . ."

Whether the mirror in the Villa of the Mysteries is a very early glass one, or whether it is an unusual silver one, its powers of reflection transcend the ordinary and venture off into a zone of allegory which we on the outside looking in are not yet equipped to comprehend. As we attempt to understand the sometimes enigmatic world of Rome, glass certainly acts as a mirror on its art, its poetry, its observations of nature, its cults and social morés, and its networks of trade and diplomacy. The images we perceive are of a complex, many-faceted society. And this is as it should be--for these images reflect back upon the complexities and antitheses inherent in glass itself. Even the derivation of the Latin work for glass -- "vitrum" has been much disputed by etymologists beginning with Isidore. He tells us:

It is called glass [vitrum] because it is, with its clearness, transparent to the vision [visus]. For in other materials whatever is contained inside is hidden, whereas in glass whatever clearness or appearance is manifested on the outside, it is the same inside, and though enclosed in a certain manner, is manifest.Thus, according to Isidore, "vitrum" comes from "videre" -- meaning "to see." Later etymologists have suggested other ideas on the subject. One proposes the Sanskrit "vithura" -- meaning "fragile, brittle, breakable thing." Another proposes a derivation from the Latin "virere" -- meaning "to be green." Still another proposes a descent from the Sanskrit "vitrás" or "vétás" -- meaning "white, light, shining."

(Etymologies XVI.16)

And so it is that wondrous glass means many things.

TEXT PANELS IN THE EXHIBITION

To Be Added . . .

FURTHER READING

These publications, all in English, focus on ancient glass in American collections. In addition, the articles on ancient glass in the Journal of Glass Studies and in Readings in Glass History are highly recommended.

Auth, Susan H.

1976, Ancient Glass in the Newark Museum. The

Newark Museum.

Goldstein, Sidney M., Rakow, Leanard S., and Rakow, Juliette K.

1982,

Cameo Glass. The Corning Museum of Glass.

Goldstein, Sidney M.

1979, Pre-Roman and Early Roman Glass in the

Corning Museum of Glass . The Corning Museum of Glass.

Grose, David.

1978, "Ancient Glass," Museum News, Vol.

XX, no. 3. The Toledo Museum of Art.

Harden, Donald B.

1936, Roman Glass from Karanis. The

University of Michigan Press.

1969, Ancient Glass: Pre-Roman and

Roman. The Royal Archaeological Institute.

Hayes, John W.

1975, Roman and Pre-Roman Glass in the Royal Ontario

Museum. The Royal Ontario Museum.

Matheson, Susan B.

1980, Ancient Glass in the Yale University Art

Gallery. Yale University Art Gallery.

Zumeta, Jay J.

1979, "A Recent Acquisition of Ancient Glass at the

Kelsey Museum," Bulletin of the Museums of Art and Archaeology,

Vol. II. The University of Michigan.