Francis Willey Kelsey

and Armenia (1919-1920)

The enormity of this particular corpus of information is impossible to document fully in the small format of this exhibition. Hundreds of photographs, letters, telegrams, diaries, and other archival pieces furnish tangible testimonies to the unfolding drama of one American archaeologist's expedition to the Near East in the short period of fragile peace immediately following the Great War.

There are many significant aspects of this drama -- its modern historical setting bounded by violent confrontations between ethnically, religiously and politically defined groups, its fluctuating national and international borders. Most important for our present purpose, however, are the historical ramifications. Although most of these documents and objects are artifacts of recent manufacture, they are the basic materials from which history is written. They are presented here as such.

The central premise of the exhibition is this: past and present are inextricably intermingled even in the thoughts of those who write the histories. Archaeologists, like the University of Michigan's F.W. Kelsey, re-construct history from the surviving bits and pieces of daily lives. Archaeologists' historical perspectives are determined by their understanding of the present. This exhibition presents a glimpse into that complex process of writing history by showing, first, something of archaeologists and their methods, and second, the archaeologist Kelsey's version of one moment from the recent past and how it was shaped by Kelsey's own involvement.

Within history, literature, and archaeology in particular, a number of recently published studies are concerned with how present preoccupations condition understanding of the past. The significance of such interaction between the past and the present is of increasing concern to contemporary scholars who trace the history of disciplines to distinguish the roads taken from those not taken, and to question the validity of previously unassailable truths. Museum presentations increasingly, on the one hand, explicate the nostalgia surrounding a given monument or culture and, on the other hand, chart the history of collecting, of art history, and of archaeology.

This exhibition explores the interlocking of past and present by focusing on two inter-related themes reflected in the two parts of the exhibition's title. Dangerous Archaeology describes an important moment in the development of the discipline by focusing on the overlapping of the last generation of scholar- explorers with the first generation of more scientifically-minded archaeologists. Indeed, the characteristics of these successive generations are sometimes discernible in one individual. The original interests of both generations lay in uncovering the roots of their own cultures. The broad description presented here includes not only the words of these archaeologists, particularly those working in the Near East during the years between the World Wars, but also the opinions of outsiders about them, their discoveries, and their opinions.

Francis Willey Kelsey and Armenia (1919-1920) delves into the special case of an extended Near Eastern expedition undertaken by the archaeologist who was so instrumental in forming the core of the Kelsey Museum's numerous holdings and in developing the study of archaeology at the University of Michigan. The focus on Kelsey in this section of the exhibition displays telling characteristics of the new breed of American archaeologists. Significantly, the expedition presented here had many purposes: scouting sites or future excavations, collecting ancient and mediaeval objects, compiling ethnological data, conducting missionary work, and carrying out various diplomatic projects. As is indicated in the exhibition's title, the focus of many of these activities was on a part of the Near East once recognized as the land of Cilician Armenia.

Thelma K. Thomas

Assistant Curator

1992

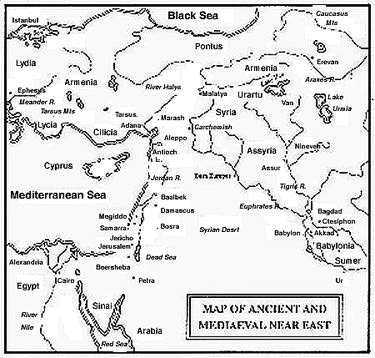

The Great War, World War I, set in motion the modern history of Europe and the Near East as new borders came to be drawn on all sides of the Mediterranean. The Near East witnessed the dissolution of the Turkish Ottoman Empire and an intensified European and American presence. The victorious Allied Powers -- the United States, France and Britain -- parceled out parts of the once vast Ottoman Empire and its resources among themselves according to various treaties. The United States received the governorship of the capital city of Istanbul (Constantinople), France received Syria, and Great Britain, much of Anatolia, i.e. the newly established Republic of Turkey. Correspondingly, Turkey and its ally during World War I, Germany, suffered territorial and strategic losses.

This exhibition's concern with Near Eastern history bridges the ancient, mediaeval, and modern periods by viewing these eras through the lens of archaeology as practiced by Westerners. This brief synopsis of the partitioning of the Near East between the World Wars sets the stage for the arrival of the archaeologists. The archaeologists went to the Near East during this period of political upheaval, ostensibly to collect ancient and mediaeval artifacts, notably those associated with the Old and New Testaments of the Judaic and Christian religious traditions. Some of the artivacts collected then are presented in this exhibition in order to illustrate clearly the gradual insertion of Near Eastern history into the life of the modern West.

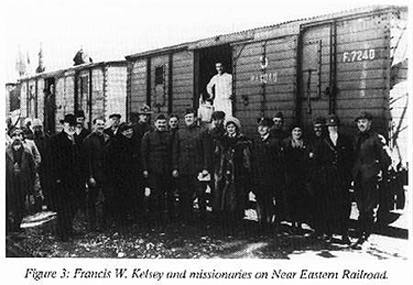

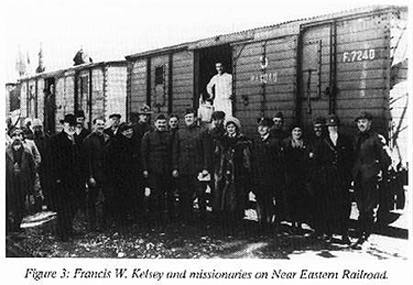

The route followed by the Near Eastern Railroad had been of great strategic importance for centuries, in part, because it allowed access to the material resources of the area. The Near Eastern railroad, along with the Trans-Siberian Railway and the Suez Canal were intended as modern versions of the three great trade routes of the middle ages. The old caravan routes which had linked East and Near East were now extended directly into Western Europe by rail and to the Mediterranean by canal.

Westerners took various advantages of their new access to the Near East via the railroad. Allied troops were sent into the region in great numbers. Missionaries expanded their numbers and their projects. Americans, in particular, were able to exploit this new opportunity because their country and its wealth had not suffered the devastations of the Great War.

The railway was of interest to archaeologist as well. Archaeologists, travelling with the soldiers and missionaries, went to survey previously inaccessible sites. Two American archaeologists, James Henry Breasted and Francis Willey Kelsey, took the Near Eastern railroad on extended expeditions during the interwar years of 1919-1920. This exhibition recounts their goals and successes as both adventurers and scientists.

Francis W. Kelsey and

missionaries on the Near Eastern

Railroad

Sir Richard Francis Burton (1821- 1890) was the archetypal adventurer. Daring, ingenuity and impropriety were his trademarks and formed the wellspring of his popularity. Although a gifted linguist and indefatigable amateur anthropologist, he was best known for his adventures. He sought the legendary source of the White Nile. He journeyed to Mecca in the disguise of a pilgrim from Afghanistan. He translated erotica such as the Kama Sutra of Vatsayana and the Arabian Nights into English. Above all, he brought the strangeness he sought in the Near East home to the West in his carefully cultivated persona and in his writings about his travels.

Western fascination with Near Eastern history was not founded solely on perceived differences between East and West, but derived also from the fact that the region was the locus for Old and New Testament events, early Christian history, and the development of Judeo-Christian religious traditions. For that reason, Western European scholarly interest in the Near East has long been focused on the origins of Western European culture. Western scholars have been noticeably less interested in the religious history of Islam and Islamic cultures. Biblical archaeology (extending from about 9000 B.C. to about 700 A.D., a few generations after the Arab conquest, and including all the lands surrounding the Mediterranean and the Near East) began early in the 19th century. The investigations of Sir Austin Henry Layard at Nineveh in the middle of the 19th century were followed by George Koldewey's excavations at Ur of the Chaldeans where the "Tower of Babel" was believed to have been found, and a continuous stream of other discoveries was made until the time of Kelsey's expedition in 1919.

Most famous of the new "scientific" archaeologists who emerged at the turn of the century was the British scholar, Sir William Flinders Petrie of the Egypt Exploration Society. Petrie excavated an enormous number of sites and developed a theory with extraordinarily practical ramifications: the study of broken pottery, the most common artifact of daily life, yields many indications of not only habitation, but also of chronology. Superimposed layers of pottery remains provide clues useful for dating the stratigraphy of a given site.

Books, newspaper and magazine articles and poems inspired by archaeological discoveries of the interwar years show how historical descriptions intended for public consumption tended to be romanticized vignettes which were interestingly, if sometimes anachronistically, combined. Even "scientific" archaeologists of the interwar period were not immune to the temptation to romanticize discoveries. They were well aware that artifacts evoke emotional responses, that they are at once concrete manifestations of history and changeable ephemera. They and other popularizers shamelessly evoked nostalgia and the desire for adventure. Those emotions continued to be the chief characteristics determining the enthusiastic reception of archaeological discoveries just as they had been for the explorers of earlier generations.

The new breed of "scientific" archaeologists working in the Near East presented a stream of discoveries to the public during the interwar years. Most well- known for its archaeological showmanship, perhaps, was the discovery of the tomb of the Egyptian pharaoh, Tutankhamun, "the boy king" (1922-31). Newspapers such as the Illustrated London News and journals such as Art and Archaeology and National Geographic kept public interest at a peak.

Significantly, it was during this time of the West's heightened awareness of the Near Eastern past that the "scientific" exploration of the earliest Christian communities began in earnest. Investigations of Biblical sites were undertaken on a massive scale during the few years between the Wars, supported, in part, by funds collected from the general public (as was the case, for example, with the British-based Palestine and Egypt Exploration Societies). Popularization was important not only for the general good and education of the public but for the funds it generated as well.

Breasted was one of the first archaeologists to travel via the Near Eastern Railroad during the interwar years. His 1919-1920 Near Eastern expedition for the Oriental Institute journeyed all the way to the railway's end at Bagdad, where he proposed to stay and carry out several research projects. While there he received a note from Gertrude Bell, an eminent British archaeologist, concerning a recent discovery made by a British officer at Dura-Europos (also called Dura-Salahiya, and Deir es-Zor). She asked him to travel there under British protection and survey the site.

Breasted was very

much aware of his position as one of the first Western

scholars to survey the site (so

much aware that he downplayed the published

information of German scholars who had

visited there previously). It is clear that

he was also aware of the glamour long since

associated with archaeological

adventure. Even as he presented thorough "scientific"

documentation of the

remains at Dura, his account of this discovery emphasized the

romance of

danger:

It was good fortune of the University of Chicago expedition to make the first dash undertaken by white men after the Great War across the desert region and the newly proclaimed Arab state, from Bagdad to Aleppo and the Mediterranean. . . .Creeping up the Euphrates as quietly as we could, and making every effort to elude the treacherous and hostile Beduin, we reached Dura-Salihiya just as the British were about to begin their retirement down river. After a hasty preliminary inspection for which we ran up by automobile from the British headquarters at Albu Kamal we found ourselves at Dura with but a single day which we could devote to making our records of the place. Without the protection of the British Indian troops it was not safe to remain a moment longer at Dura, and this first publication of the Oriental Institute represents a single day's field work of the expedition. [Breasted's italics]More importantly as concerns this moment in the development of Near Eastern archaeology, Breasted's point of view remained typically and essentially Western insofar as he saw his task as an Orientalist archaeologist to trace the Eastern origins and evolution of European and American civilization. Breasted successfully discovered the West in his dash across the Near East:

(J.H. Breasted, Oriental Forerunners of Byzantine Painting, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1924, pp. 1- 2)

It is a matter of gratification to its members that the first volume of a series to be known as the Oriental Institute Publications should contain these materials which so unequivocally illustrate the process of culture transition from the Orient to Europe. The recognition of this transition is daily revealing to modern men that there is no sharp cleavage between the Near Orient and Europe. The successive rise of both from prehistoric savagery has been one evolutionary process, the recovery of which will enable us to write the coherent and unified story of mankind. Writing these words, as I do, overlooking the hills of Tuscany but a few hours away from Ravenna, and contemplating the roofs and towers of Florence spread out below this historic villa where it is believed by many that Boccaccio found the scene of his immortal Decamerone tales, it seems peculiarly fitting that these prefatory words should be penned in the midst of surroundings which reveal at every turn how great a part in the revival developed so richly here in Florence, and especially the art of painting, was based to no small extent upon that of Byzantium, of which we must evidently recognize the ancestry in the wall paintings of Dura.Breasted's publication of those frescoes as Oriental Forerunners of Byzantine Painting helped to shape the field of early Byzantine archaeology and art history as we know it today: subsequent excavations at Dura Europos, a military outpost and caravan site on the Euphrates, furnished our oldest examples of Christian art; later studies investigated the ways in which the art of Dura was seen to lead to the development of Western Christian art.

Villa Palmieri

Florence Italy

June 1, 1923

(Breasted, 1924, p. 8)

We must beware and not limit the field of archaeology too much; the arrow head found around Ann Arbor, the walls in Central America -- almost as much of a puzzle today as a hundred years ago -- the relics of the Mound Builders, all these fall in the range of archaeology just as much as Greek and Roman relics. There is no object that bears the imprint of human mind, that shows purposeful expenditure of human energy in past ages, that does not come under this science. This opens an immense field, a bewildering one; it may seem strange to compare the statues of Phidias with an arrow head, yet each shows the purpose of the maker; the same set of muscles made the two objects; they have something in common. Such is the breadth of the subject, that while the limits are fairly clear, it is hard to fix them. . . . Again, where does the ancient stop and the modern begin? This is equally hard to answer; in general, men will extend it to the close of the classical period. But too we have the Christian archaeology later; this has a wide range running on into the middle ages and even into modern times." [Italics added]Kelsey and other archaeologists of the new breed considered themselves to be scientists, and more. They intended to provide a link between ancient history and the modern world as well. He and his colleagues saw it as their duty, as citizens of the word, to involve themselves in political and military matters as well as in their more abstract, scholary pursuits. Both aspects of their archaeological investigations were linked by their own cultural backgrounds.

(from F.W. Kelsey's unpublished Lectures on Archaeology, 1896, in the collection of the Kelsey Museum Library)

Kelsey's 1919-1920 expedition to the Near East, undertaken via the reopened railway like Breasted's expedition of the same year, is presented in detail in Part Two of the exhibition. It is important to note in this context that Kelsey's archaeological and other interests were located squarely within the Graeco- Roman continuum. In all ways, Francis Kelsey remained a classicist, more specifically a romanist, unlike the Egyptologist-Orientalist Breasted. Kelsey never travelled any further east than Aleppo. The Mediterranean was at the center of his map of the ancient world. The sites Kelsey chose for excavation form a ring around the Mediterranean, in Syria, Egypt, and Tunisia: Kelsey traced the rise of Greek and Roman cultural dominance at these sites. As a classical scholar in the Near East he was not so much interested in the evolution of ancient Near Eastern into Western culture as he was interested in finding traces of Greece and Rome in the Near East.

Whereas the opinions of James Breasted, Kelsey's contemporary and colleague, were sought on political and military matters by various powerful individuals, Kelsey's great energy and determination were spent without attracting particular notice. His articles on the Near East, based on his travels in Syria and Turkey, were published in archaeological journals or local newspapers, rarely in the national or international presses.

Feisal�s reception in Damascus

As explained in a letter of 1918, Kelsey's 1919-1920 expedition had several goals: to visit important archaeological sites previously or currently under investigation, to photograph and survey possible sites for future University of Michigan excavations, to photograph monuments and artifacts for later study at the University, and to collect artifacts--chiefly ancient and mediaeval manuscripts of Christian cultures of the Near East. In addition, Kelsey intended to photograph persons of Near Eastern and Eastern European ethnic origin. Outside the realm of archaeology proper, Kelsey also planned to photograph missionary efforts and to write about them.

Ultimately, the expedition had a smaller staff than Kelsey had envisioned. He had no Orientalist and no missionary physicians on staff. The party consisted of a photographer, G.R. Swain, and a photographer's assistant, Easton T. Kelsey (Francis Kelsey's son; at some stages they were joined by Francis Kelsey's wife, Isabel). Despite the small staff, the expedition was successful in each of its numerous endeavors. It did manage to start early enough to take advantage of the aftermath of the Great War; that is, to travel with military protection and aid, and to buy rare manuscripts at prices forced low by the desperate positions of their owners.

While abroad Kelsey was moved by the horrible realities of the situation upon which his abstract speculations had been based. The work of the Red Cross, the Near East Relief, the Young Men's Christian Association and other similar organizations consumed much of his time. He not only travelled with people who worked for these charitable organizations, but also visited their projects and saw for himself the refugee camps, orphanages and training schools for Syrians, Greeks and Armenians. He spoke extensively with the missionaries and with their charges, collecting information for a series of newspaper and journal articles. Circumstances impelled him to involve himself in various political and military activities as well.

Part Two illustrates the diverse projects of Kelsey's 1919-1920 Near Eastern Expedition by two thematic groupings of letters, photographs, and artifacts. The first group treats the whole of the expedition according to its itinerary. The second group focuses on Kelsey's involvement with Armenia. As in Part One of this exhibition, the brief identifications for each photograph are taken from the notes of Kelsey and Swain.

The fact that the Near Eastern Expeditions began in Europe is also indicative of Kelsey's special scholarly interest in the Roman Empire. The first investigative visits of the expedition were made in France at locations which had been, two thousand years before, the battlefields of Julius Caesar, in order to see what remained of the ancient sites of combat. Kelsey and those in his party were struck by the horrific irony that those ancient battlefields bore traces of the recent Great War as well.

In addition, while in Europe Kelsey acquired rare Christian manuscripts from the Near East which had been dispersed as a result of the recent hostilities.

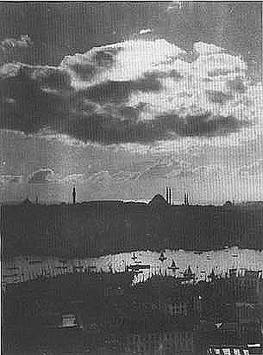

The first stage of the Near Eastern Expedition was in Istanbul. True to his background as a classicist, Kelsey consistently sought evidence of the city's Roman past.

During the middle ages Istanbul had been the premier capital city of the Eastern Roman, or Byzantine Empire (330 -1453 A.D.). The Byzantine Empire was the longest-lived and most extensive Christian empire of mediaeval times, and its capital supplanted Rome in secular and, for much of the Near East, in religious authority. Old Rome was, in effect, replaced. In the face of opposition by the powerful pagan senatorial class of Rome, in 324 A.D. the Christian Roman emperor Constantine moved his capital from the city of Rome to Byzantium, a military outpost on the Bosporos. There he founded a Christian city which was named New Rome, but which was called, after his illustrious self, Constantinople.

Kelsey, along with most of his contemporaries, continued to call the city Constantinople rather than Istanbul, the name used during later Ottoman rule (1453-1918 A.C.) up to the present day. His informed selection of the name Constantinople is an indication that, in his mind, his itinerary took him from Old the New Rome.

Skyline of Istanbul, Turkey

Church of Saint Sophia, Istanbul, Turkey

"Saint Paul's Gate," Tarsus, Turkey

Interior of the Great Mosque, Damascus,Syria

Predynastic Egyptian amulet in the shape of a lion's head

Middle Kingdom Ushabti

Roman period mummy mask

"Cave of the Apocalypse," Patmos, Greece

Of all the time Kelsey spent in Turkey, his shortest stay was in the south, in Cilicia. However, he expended a great amount of time and energy on behalf of the Christian communities there, which were, largely, Armenian. In Cilicia, as elsewhere, he collected artifacts and photographed monuments of its ancient and mediaeval past, its modern inhabitants and examples of the Western presence--missionaries, schools, and relief efforts. Kelsey's archaeological interests in Cilicia paralleled his interests in other regions he surveyed during this expedition. He travelled to modern towns as well as to ancient sites. In his search for evidence of daily life and death as it spanned the centuries, he had the exbedition photographer document the changing countryside, people at work, "ethnological types," churches, cemeteries, etc. Contributing to the intensification of Kelsey's efforts on behalf of the Armenians of Cilicia were a series of violent incidents which occurred during the expedition.

Long before its foundations as Greater Armenia, the region surrounding Lake Van and Mount Ararat had been a point of cultural contact for the ancient Near East. Anatolian, Indo-European and other migratory tribes converged here with the local Urartian population. After the collapse of the Urartian kingdom toward the end of the 7th century B.C. the new ethnico-political entity of Armenia began to emerge. The first independent Armenian dynasty claimed its independence from the rule of the Greek Seleucids only in the 2nd century B.C. Throughout the later history of Greater Armenia various local and foreign powers sought to dominate its main resource, which was the northern trade route across Asia Minor. Armenians maintained a precarious, limited and often interrupted control only by the prudent political powers. In the 11th century, as the Seljuk Turks routed the Byzantines and won governance of Greater Armenia, the Byzantines sought to protect their dwindling territory by relocating Armenians to the provinvce of Cilicia.Cilicia and Greater Armenia

Armenians settled in the mountains and valleys of Cilicia and there established

the last independent Armenian kingdom of the middle ages. Architectural

monuments and other artifacts testify to the three-hundred-year flowering of the

Cilician Kingdom of Lesser Armenia. Located at the easternmost corner of the

Mediterranean, in fertile agricultural land, on the southern caravan route, and

controlling southern access into central Anatolia, Cilicia had always been of

great strategic importance to the Near East. From their fortified mountain

castles the Armenian barons guarded the passes through Cilicia and controlled

the overland trade to and from Asia. This was the source of the kingdom's

wealth and its knowledge of East and West. Visitors from all over the known

world -- Byzantine Christians, Muslims from the East, and Crusaders from

Western Europe on their way to the Holy Land -- passed through Cilicia. Cilician

Armenia created its own culture, an interpenetration of Armenian traditions and

Byzantine, Islamic and Western influences. Eventually weakened by warfare

with its neighbors and invaders, the kingdom fell to the Mamelukes in 1375.

Armenians settled in the mountains and valleys of Cilicia and there established

the last independent Armenian kingdom of the middle ages. Architectural

monuments and other artifacts testify to the three-hundred-year flowering of the

Cilician Kingdom of Lesser Armenia. Located at the easternmost corner of the

Mediterranean, in fertile agricultural land, on the southern caravan route, and

controlling southern access into central Anatolia, Cilicia had always been of

great strategic importance to the Near East. From their fortified mountain

castles the Armenian barons guarded the passes through Cilicia and controlled

the overland trade to and from Asia. This was the source of the kingdom's

wealth and its knowledge of East and West. Visitors from all over the known

world -- Byzantine Christians, Muslims from the East, and Crusaders from

Western Europe on their way to the Holy Land -- passed through Cilicia. Cilician

Armenia created its own culture, an interpenetration of Armenian traditions and

Byzantine, Islamic and Western influences. Eventually weakened by warfare

with its neighbors and invaders, the kingdom fell to the Mamelukes in 1375.

Cilicia became part of the Ottoman Empire in the 15th century, with Armenians

maintaining a presence in the trading cities. Along with the Syrian and Greek

Christian communities of the empire, Cilician Armenians generally survived and

prospered until the beginning of this century. During the Great War, as the

Ottoman Empire collapsed, relocation marches drove much of the Armenian

community out of the area. Survivors returned to Cilicia under the promise of

British and French protection. In 1920, fierce fighting broke out. The Western

allies abandoned the military struggle, and the Armenian communities of Cilicia

were ultimately driven south to Syria and Lebanon in the winter of 1920. (Many

members of the Armenian communities of southeastern Michigan who

immigrated from Syria and Lebanon have roots in the region of Cilicia.)

Cilicia became part of the Ottoman Empire in the 15th century, with Armenians

maintaining a presence in the trading cities. Along with the Syrian and Greek

Christian communities of the empire, Cilician Armenians generally survived and

prospered until the beginning of this century. During the Great War, as the

Ottoman Empire collapsed, relocation marches drove much of the Armenian

community out of the area. Survivors returned to Cilicia under the promise of

British and French protection. In 1920, fierce fighting broke out. The Western

allies abandoned the military struggle, and the Armenian communities of Cilicia

were ultimately driven south to Syria and Lebanon in the winter of 1920. (Many

members of the Armenian communities of southeastern Michigan who

immigrated from Syria and Lebanon have roots in the region of Cilicia.)

Christianity defines the chief part of this cultural core. In a way, Armenian culture has no pre-Christian history. King Trdat, the first Armenian Christian king, while engaged in the ancient Near Eastern, particularly Sassanian royal activity of hunting, experienced a vision of the cross of Christ's crucifixion, and converted on the spot. This and other Armenian myths about their conversion to Christianity served to define the people as a Christian community. These tales were written in an alphabet created around the turn of the 5th century A.C. in Edessa, Syria, where the Syriac written language was being shaped concurrently. Armenian literature developed at an enormous rate during the 5th and 6th centuries and incorporated Christian literary traditions of, for example, hagiography (writings about martyrs and saints) and exegesis (scriptural interpretation). Not only Armenian literature but all of Armenian culture developed within the international setting of early Christianity.

Certain artisitic forms, however, developed with an intensity unique to Armenia. Mediaeval manuscripts offer a chain of evidence of the determined continuity of Christian Armenian culture despite disruptive changes. The initial letters of chapters and sentences in lavish hand-produced manuscripts were treated to elaborate ornamentation that transformed the letters into plants, figures, animals, abstract patterns and other hybrid creations. A distinctively Armenian style in representational arts is typically vibrant and ornate. No element is merely functional. Frames for scenes, for example, serve as both boundary and ornament. Characteristically, forms of clear, flat colors are outlined in black, then shaded and lightened to white so as to create an effect of shimmering light, agitated energy. Lines, often freed from the simply descriptive, make dynamic abstract patterns of whorls, waves and other almost animate shapes. Improvisations on basic forms are drawn out and repeated with infinite variations: a leaf, for example, may be split into two parts, those parts then reversed, smoothed, lengthened and interlaced.

Khatchkars are a type of carved plaque made only in Armenia, principally for cemetery use, but generally commemorative in function. The earliest khatchkars date from the 9th century A.C., but the form found its greatest expressions in the 13th century. Designs on khatchkars are essentially crosses, often elaborated by the abstract intricately interlaced patterns so often found in other Armenian arts.

Armenian architecture of the middle ages, known to us mainly from the remains of churches and castles, is also distinctive in style. Built of ashlar blocks of local tufa (a volcanic stone, often reddish in hue) over concrete cores, the churches tend to compact geometric masses which rise dramatically from cross-shaped ground-plans to high domes supported by squinches. Cross shapes appear to have functioned as markers of faith since the legendary conversion of King Trdat, and are ubiqitous in Armenian art. Other especially Armenian imagery, based on conversion myths and local history for example, were often incorporated into the more standard Christian compositions based on the Old and New Testaments.

Although Kelsey did not travel north to Greater Armenia, he was well aware of the dispersal of Armenians throughout the whole of Turkey, as well as in Palestine, Syria, Egypt, Eastern Europe and North America. Consequently, Kelsey documented the modern Armenian communities and archaeological remains of past Armenian communities not only in Cilicia, but also in all the regions through which his journey took him.Kelsey's Archaeological Interests in Cilicia

Ruins of an Armenian church, Konya Turkey

Kelsey's interests in Armenia were very much influenced by his own background as a Christian of Western European descent. Since mediaeval times, Western presences in the region had taken their cues from the status of Christians there. A scenario similar to that played out during the Crusades was re-enacted in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Western missionaries, chiefly Protestants, looked to ancient Jewish and Christian nations of the Near East as the cradles of modern Christian civilization. The missionaries were followed by Western military might, wielded to control and redistribute Near Eastern territories to the descendents of those ancient nations. Whereas Britain established the state of Israel in Palestine, America's President Wilson drew up an initiative to carve a 20th-century Cilician nation out of Turkish territory.

International political developments were of great interest to Kelsey, but his more successful efforts were on a less grandiose scale. He documented the work of missionaries associated with Near East Relief and the Young Men's Christian Association, American-based missionary organizations that worked to relieve shortages of food as well as to provide food, shelter and professional training to the Armenian survivors of hostilities in Cilicia, as well as to the Christian World War I refugees of Syria and Greece.

One incident in particular served to highlight the danger and urgency of the situation: two American missionaries and their Syrian driver were ambushed, shot and killed on the road between Aintab and Aleppo. Kelsey had something of a personal stake in the killings of Perry, Johnson and Zakie because Swain had photographed Mr. Perry and other missionaries only weeks before and because Zakie had driven Kelsey and Swain along the same road, again only a few weeks before. Although Kelsey had been quite frightened when travelling that road because of rumors of random violence, his party had passed through safely and had trusted their safety to their identity as Americans. Now that Americans' sense of immunity had been demolished, the direness of local conditions became frighteningly clear.

Tales of siege warfare at the towns of Aintab, Urfa and Marash continued to push Kelsey into action while he remained secure outside the country, his expedition having gone on to Syria and Palestine, and to Egypt. During these latter months of the expedition and after, Kelsaey put together documentary and photographic "exhibits" which recorded these and other incididents of violence directed against missionaries and Armenian communities in the Near East. These he sent to political leaders and high-ranking military personnel as well as to prominent residents of Michigan and the rest of the United States. While his articles and exhibits were published in the local press, University of Michigan and missionary publications, national and international recognition eluded him. His version of these events never found widespread publicity.

Kelsey's expedition took place at a pivotal moment in the history of archaeology. He must be counted among the first-generation scientist-archaeologists who still clung to the roles of adventurer-explorer and statesman. They attempted both to understand and to participate in the writing of Western history. Kelsey and his contemporaries, like the Orientalist Breasted, wrote histories filtered through notions of their own cultural origins. They traced the glory of the West, endowing it with the most desired origins, whether found in the art of Dura Europos or Constantinople.

The development of the discipline of archaeology continues. In archaeology, as in art history and other fields of history, there is a new, mounting awareness of the enduring ramifications of the forces at work in the formation of scholars like Kelsey and Breasted. Research into the growth of these fields is bringing forth information about the biases inherent in our histories as well as critical methodologies for further study of diverse cultures and points of view other than our own. A pure science of archaeology escapes us in so far as our present situations continue to condition our understanding of the past. Kelsey, Breasted and others of the first generation of scientific archaeology were bound by their own points of view, as were their predecessors, and as are their successors.

Consider the following comments by scholars from the 19th century until the present as examples of the ways in which archaeologists and other historians have long been cognizant of the self-serving uses of history:

"To everyone who looks back on his past life," wrote the English antiquarian Benjamin Thorpe in 1851, "it presents itself rather through the beautifying glass of fancy, than the faithful mirror of memory; and this is more particularly the case the further this retrospection penetrates into the past. . . . "Among nations," Thorpe continued, "the same feeling prevails. They also draw a picture of their infancy in glittering colors. [italics added]. . . Man's ambition is two-fold: he will not only live in the minds of posterity; he will have also lived in ages gone by. He looks not only forward but backwards also; and no people on earth is indifferent to the fancied honor of being able to trace its origins to the gods, and of being ruled by an ancient race."

(quoted in Neil Asher Silberman's Between Past and Present. Archaeology, Ideology, and Nationalism in the Modern Middle East, New York, 1989, p. 1)

* * * * *

As [Darwin and] the natural scientists have labored on, the physical origin of man from lower animals has become far clearer. But between the historians and the natural scientists there has been a "great gulf set," with the result that we now have on the one hand the paleontologist with his picture of the dawn-man enveloped in clouds of archaic savagery, and on the other hand the historian with his reconstruction of the career of civilized man in Europe. Between these two stand we orientalists endeavoring to bridge the gap. It is in the gap that man's primitive advance passed from merely physical evolution to an evolution of his soul, a social and spiritual development which transcends the merely biological and divests evolution of its terrors. It is the recovery of these lost stages, the bridging of this chasm between the merely physical man and the ethical, intellectual man, which is a fundamental need of man's soul as he faces nature today. We can build this bridge only as we study the emergence and early history of the first great civilized societies of the ancient Near East, for there still lies the evidence out of which we may recover the story of the origins and the early advance of civilization, out of which European culture and eventually our own civilization came forth. [italics added]

(James Henry Breasted, "The Task of the Orientalist and Its Place in Science and History" in The Oriental Institute, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1933)

* * * * *

Archaeologists are invited to consider critical theory by evidence that archaeology in some environments is used to serve political ends and by the growing controversy over the ownership and control of remains and interpretations of the past. The claim of a critical archaeology is that seeing the interrelationship between archaeology and politics will allow archaeologists to achieve less contingent knowledge. [italics added]

(Mark P. Leone, Parker B. Potter, Jr., and Paul A. Shackel, "Toward a Critical archaeology" in Current Anthropology 28/3 (June 1987): 283-302)

PART ONE Archaeology and the Near East

A BRIEF NEAR EASTERN CHRONOLOGY

Sumer beg. 5th millenium BC

Akkad beg. 5th millenium BC

Ur beg. 4th millenium BC

Babylon after 2129 BC

Hittites beg. 2nd millenium BC

Persian Empire ca. 555-330 BC

Antigonid Empires 4th c.-1 BC

Seleucid Empire 4th c.-1 BC

Parthians 1-2 c. A.D.

Roman Empire 1-4th c. AD

Sassanians 3-6th c. AD

Byzantine Empire 6-11th/15 c. AD

Arab Caliphates 7-12th c. AD/AH 1st-5th c.

Crusader Kingdoms 11-12th c. AD

Seljuks 11-15th c. AD

Ottoman Empire 15th c.-1918 AD

Republic of Turkey c. 1924 to the present

Archaeologists work with all manner of data: artifacts such as coins and pottery, and written and photographic records of archaeological investigations. The above-mentioned types of archaeological data as well as some of the tools used to gather that information are shown and described as a means of providing a glimpse into the archaeological mind.Archaeological Evidence: Coins

The coins displayed here provide tangible evidence of Near Eastern ancient and mediaeval eras, of their political powers, and of the important personalities which controlled those powers. In general, coins provide much-needed information concerning political power and economic dominance. Rulers name and portray themselves on coins, often giving themselves the most ostentatious, the most unequivocally expressive titles and symbols of power. The dates and locations of the production of coins tell a great deal about the concentration and distribution of wealth, and about international routes of trade. Coins are the bits of official metal painstakingly acquired and sent out by tax-payers, to tax-collectors, on the way to provincial and metropolitan treasuries. Discoveries of coins enable archaeologists to determine the level of prosperity of a given area as well as to date stratigraphic contents of the sites in which the coins were found.

Engine cab of the Berlin-Bagdad train

Photography has played a very important role in archaeological documentation since its introduction into the documentary record towards the end of the 19th century. An obvious means of presenting far-off lands to armchair travellers, photography became a recording tool for scientists of all stripes. F.W. Kelsey and his contimporaries in archaeology immediatle recognized the contributions photography could make not only for documentation, but also for research and teaching purposes.Archaeological evidence: Photography

A new professional in the discipline of archaeology, the expedition photographer recorded new discoveries from the moment of their appearance, and documented each step in the field. George R. Swain was the photographer for this and other Univerity of Michigan expeditions to the Near East. Accompanied by Easton T. Kelsey, the son of Francis W., he took many hundreds of photographs. Some were laboriously produced seven-by-eleven inch negatives of exceptionally clear quality; others were quickly snapped shots made with a Kodak; all were meticulously catalogued and described. (Due to the deterioration of their negatives, all photographs have been reshot and reprinted.) The detailed photographic records of Swain and Kelsey have been of inestimable help in reconstructing the expedition. Their descriptions provide the basis of the labels used for the photographs in this exhibition.

An independently-affiliated motion-picture maker, Carl Wallen, accompanied the Expedition on a part of its journey. Unfortunately, none of the films made by Wallen on the expedition have been recovered although mention is made of them in the diaries of Kelsey and Swain.

The finely machined tools displayed here date from the early decades of this century and exemplify the quick adaptation of technology from other professions to the new scientific discipline. The transit theodolite, for example, was used by land surveyers and the archaeologists to measure angles of the topography.Archaeological tools

Since pre-historical times, the universal material of clay -- kaolin-laden earth -- has been molded into useful shapes, then hardened to form relatively permanent structures. Ceramic objects were and still are often used as vessels for containing liquids because fired clay is not porous, and used as lamps because clay is non-flammable, and as inexpenxive small toys and figurines because clay is cheaply and easily mass-produced by means of molds.Archaeological evidence: Clay wares

Thanks to the efforts of Flinders Petrie, pottery is recognized as being essential to the basic archaeological task of assigning dates. The clay, the shapes of clay vessels and lamps, and markings on them often indicate where a pot was made. Moreover, shapes fit into chronological sequences for which dates can be assigned. In addition, the distribution of pots with similar shapes, or profiles, over a wide area, for example, is a frequent indicator of far-reaching trade (usually of the contents of pots rather than the pots themselves; only fine ceramic wares were traded for their own value); the concentration of a wide range of shapes of pottery within a small area, on the other hand, might tell of long-term inhabitation of that area.

A Personal Interpretation of an Archaeological Discovery: Christian Lamps of Clay from Carthage

Dry, academic concerns such as pottery fragments have never captured the imagination of the public. Instead, the imagined inner lives of the people who used them enrich their otherwise limited visual appeal. In the poem reproduced below, for example, humble artifacts of clay, small and inexpensively mass-produced lamps from late Roman Carthage (Tunisia), inspired a vision of the illuminating force of the emergence of Christianity. Poems inspired by archaeological discoveries were a convention in the magazine Art and Archaeology, routinely included following each article.

OLD LAMPS

Through what lone visions did your clear flames shine,

O darkened lamps of dim, forgotten years?

What have ye seen of silent midnight tears

Falling before Love's sad and voiceless shrine;

What aged prayers, that towards a light divine

Trembled across the threshold of the spheres;

What flattering breath of song that no heart hears

Stirred the dim shadows of your strange design?

Ah, now for me the lights of dreams ye hold

Safe from the world! Your cressets of white fire

Through darkened windows of the west aspire

To vast new lights and shadows of pale gold,

Bright, far and strange, yet tender with the old,

Soft ways of peace, and all the heart's desire!(Edith Dickens in Art and Archaeology 21 (1926): 66; following the article "Carthage: Ancient and Modern" by F.W. Kelsey, pages 55-66)

The die-hard classicists, and those teachers of ancient history who had been trained in the tradition that the cultures of Greece and Rome were the result of some divine spontaneous combustion, found it difficult, often impossible, to accept the author's revolutionary reappraisal of the importance of the orient in the development of civilization. It was only to be expected, too, that fundamentalists everywhere, especially in the southern States, should resent his evolutionary approach to history, an attitude which received curiously antithetical expression in 1925 at the famous "Monkey Trial" of a young biology instructor named J.T. Scopes who had committed the crime of teaching evolution in Tennessee. Clarence Darrow, who defended him, cited Ancient Times in substantiation of the truth of such teaching; while William Jennings Bryan pilloried the book as a consummate example of the kind of iniquitous falsity which he insisted was destroying American religious faith.Breasted's controversial contribution to archaeology

Science and adventure mingled in the new breed. Just as for archaeological discoveries, personalities in archaeology gained popularity for their associations with adventure (witness the fictional charismatic American archaeologist of this period, Indiana Jones).One perception of an archaeological narrative: the final conflict at Armageddon becomes the battle at Megiddo

Breasted's popularity outside academia, although based primarily on his publications, was phenomenal as is shown in the quotations collected here.

Breasted was lionized by military commanders because of his studies of ancient battles.

The battle of the Egyptians versus the Hittites at Armageddon caught the attention of Great

Britain's Lord Allenby (who had under his command T.E. Lawrence, "Lawrence of

Arabia," once a student of Near Eastern archaeology -- specializing in Crusader castles, and

excavating at Carchemish -- before called to military service):

"You know, for you have very fully written of it," Allenby said, "how Thutmose III

crossed Carmel Ridge, riding through the pass to meet the enemy in a chariot of shining

electrum. We had your book with us, and we had just read the account of it, so we knew

the dates: Thutmose went through on the 15th of May over 3,000 years ago, and on the

same day I took Lady Allenby for the first time to see the battlefield where we beat the

Turks, and like Thutmose III, we also went through in a chariot of shining metal -- for our

machine had wheels of aluminum and was all covered with polish[ed] metal. So she saw the

scene of our victory on the anniversary of the earliest known battle there, and also

approached it in a chariot of glittering metal. I wanted her to see it, for as I have told you

before, I took my title from there -- Allenby of Megiddo. . ." (quoted in Charles Breasted,

Pioneer to the Past. The Story of James Henry Breasted, Archaeologist. New York,

Charles Scribner's Sons, 1943, pp. 311-2)

Breasted's scholarship intrigued another influential commander: the American, Theodore Roosevelt.Ancient History of the Berlin-Bagdad Railway

Moreover, Colonel Theodore Roosevelt said: "I'm convinced the War will be won in the Near East -- by blasting the Germans' Berlin-to-Bagdad dream. After reading your Ancient

Times, I was impelled to re-read the description in your History of Egypt of the strategic

importance of Kadesh in the control of northern Syria, and of Ramses II's battle with the

Hittite king, Metella, who almost defeated him, and really ought to have done so. I studied

detailed maps of the whole region, and it seemed to me obvious that if control of Kadesh

once spelled control of northern Syria, then surely that seizure today of Alexandretta,

followed at once by a northeastward thrust cutting off the Bagdad railway, would

simultaneously strike the Germans and the Turks at the most vulnerable point in their flank,

isolate their southern forces, and by achieving control of Syria and Palestine, destroy the

Berlin-to-Bagdad plan."

(Charles Breasted, Pioneer to the Past. The Story of James Henry Breasted,

Archaeologist. New York, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1943, pp. 233-4)

PART TWO Kelsey's Expedition and Armenia

ITINERARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN EXPEDITION TO THE NEAR EAST

Europe September 1919 to December 1919

Turkey December 1919 to January 1920

Syria January 1920

Palestine January to February 1920

Egypt February to March 1920

Greece May to June 1920

Europe June to October 1920

Ann Arbor return: October 1920

9. Turkey, "Constantinople"

10. Turkey, Cilicia

11. Syria and Palestine

12. Egypt

13. Greece

14. Kelsey and Armenia

ANCIENT AND MEDIAEVEL ARMENIA: A CHRONOLOGY

Dynasty of Artaxias 190-2 BC

Foreign Dynasty 2 AC-53 AD

Arsacid Dynasty 53-429 AD

Persian Marzpan 430-634 AD

Byzantine Governors 591-705 AD

Arab Domination 654-861 AD

Bagratid Dynasty 885-1045 AD

Cilician Kings 1080-1375 AD

CHURCH OF THE HOLY CROSS AT AGHT'MAR This church on Lake Van was built in 915-21 AD under the patronage of King Gagik of Vasparakhan and remained in continuous use for a millenium until after the First World War, suffering no substantial change except for gradual deterioration. Like most Byzantine churches of the Near East the plan of the Church of the Holy Cross at Aght'mar is cruciform; however, many aspects of its construction are particularly Armenian. The plan at ground level is quatrefoil in shape with semi-circular niches filling the diagonals. At cornice level, the niches are covered over by squinches which are shaped as sections of cones, and seem to have been introduced in Armenian architecture as a means of adapting a square to a circular shape. (Squinches, another particularly Armenian architectural support system constructed of intersecting arches, furnished sophisticated geometrical solutions to structural problems. In fact, the great vault builders of the mediaeval Christian Near East appear to have been Armenians. As much is indicated by the fact that the Armenian architect Trdat was called to Constantinople in 989 when the western arch and half-dome of the cathedral of Hagia Sophia collapsed.) On the upper level of the church at Aght'mar is a high polygonal drum surmounted by a dome, its conical shape typical of Armenian architecture.

Slight elongations to the east and west enhance the clarity of the symbolic cross shape and emphasize the location of the sanctuary within the eastern bay. The building was endowed with additional meaning by its decoration. Although the interior frescoes are not preserved, the sculptures carved in high relief on the exterior are in excellent condition.

17. Kelsey's View of the Incidents in Cilicia