The dispersal of pottery from Egypt throughout Western Europe and the Near East is, in part, attested to by small inexpensive terracotta flasks from the renowned pilgrimage site of St. Menas. On these flasks the saint is shown standing with his arms outstretched in prayer, beween two crosses and the two camels that carried his body to his final resting place. Pilgrims from across Europe and Asia Minor travelled to the holy shrine of St. Menas in the pilgrimage city of Menapolis, to worship at the saint's tomb, and to carry away with them in such flasks as these the healing oil or water that had been in contact with the tomb. These were dispensed and sold to pilgrims as the tangible and enduring blessings of their pilgrimages.

Christian Funerary Stele

Relief plaque and Cross Pendant .

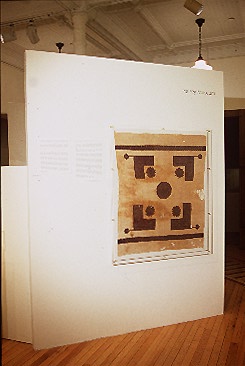

Textiles, an important Egyptian production since pharaonic times, constitute the greatest portion of the Kelsey Museum collections, numbering approximately 10,000 items. Most of these are fragments of garments and household furnishings woven of wool, linen and, more rarely, cotton and silk; they range in date from the Pharoanic, Ptolemaic, Roman and Byzantine periods to the later periods of Arab-Islamic rule of Egypt. The Byzantine collection includes examples of plain- and tapestry-woven, and embroidered textiles which draw upon a wide variety of styles. The decorations of these textiles are equally varied, presenting abstract and geometric patterns, as well as figural, vegetal, and animal motifs. Religious content is not always evident although certain examples represent mythological scenes, while others may be identified as Christian by sacred symbols and scenes, angels, saints and other holy personnages.

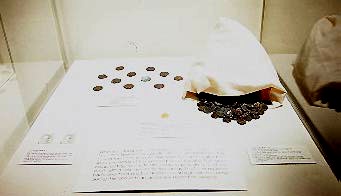

Coins comprise the chief part of the Kelsey Museum's Byzantine holdings and constitute half of the total number of items in all the Museum's collections. Most came into the Museum from its excavations; some were acquired through the donations of coin collectors; very few were purchased.

During antiquity and the middle ages, coinage provided the principle, the only relatively permanent currency for exchange. Imperfections in the coins (e.g. curvature and off-center compositions) reflect that the coinage was struck by hand. Byzantine coinage was strictly controlled by the government, produced at mints under imperial control. Mint marks (used from the later third c. CE) areletters and symbols which tell where the coins were made. Mint marks are particularly helpful in that many coins are often found far from their place of origin. Coinage served another more propagandistic purpose as well. The images and inscriptions impressed on a coin communicated imperial messages throughout the empire. Imperial portraits, following a Roman tradition set by Julius Caesar, are the most common type of coin image. These are usually bust-length and include the emperor's name and titles. The other side of the coin may present personifications of abstract concepts (Peace, Good Fortune, Wisdom, Victory) with which the emperor identified his reign, or his conquests, and members of the imperial family. Religious imagery was another staple of coin imagery. Mythological scenes, and attributes of the gods are common during the late Roman period. Increasing in frequence from the early fourth century, following Constantine's legalization of Christianity, was the sign of the cross.

The Byzantines struck coins in gold, electrum (an alloy of silver and gold, silver and silver alloys, and bronze. Denominations were based on size and metal content. Gold coins were the most precious, yet silver is less often preserved than gold. Bronze coins were most common, but these corrode easily and survive in poor condition.

Constantine reformed the Roman coinage system, in response to inflation (reflected in the debasement of metals used in coinage), introducing the solidus (called nomisma in later Byzantine times; known in the medieval western world as the "bezant") and its fractional denominations. Change could be made by cutting a coin into smaller pieces when smaller denominations were not available.