Identifying the Skeletons

The analyses of the skeletons from Oplontis are not yet complete. At present only the age and sex of the victims are known. Among the 34 skeletons of persons who appear to have been well off, both male and female skeletons were among the nine that were found with jewelry. One theory is that these nine represent the proprietor of Oplontis B and his or her family. One scholar has gone so far as to suggest that the woman (skeleton 27) who had more jewelry and money than any other was the owner of the complex. Unfortunately, these speculations cannot be substantiated by the available evidence. The individuals who died in room 10 could have been residents of Oplontis B or refugees from the surrounding area, or a combination of the two. Yet the small number of people who were found with jewelry in room 10 suggests that their jewelry served as a mark of their social or economic status.

Gold Earrings

A Selection of Coins Found with Skeleton 27

Everyday Luxury

Objects from Oplontis B

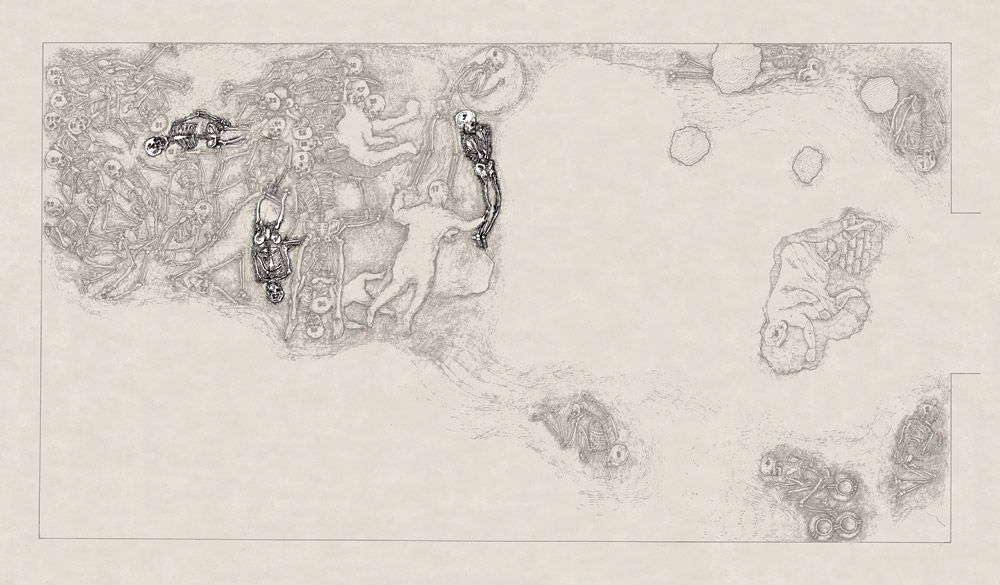

During the excavation of room 10 of the Oplontis complex, begun in 1984, archaeologists found two groups of skeletons of people who had sought refuge from the eruption. The first group, found closest to the entrance to the room, consisted of 34 skeletons alongside rich finds of coins, jewelry, and household goods. This is the group that appears in the drawing shown here. A second group of 20 skeletons was excavated several years later at the back of the room. These had no money or jewelry but only lanterns and tools. Some scholars have proposed that this group consisted of slaves, segregated from their owners even in death.

Luxury and Status

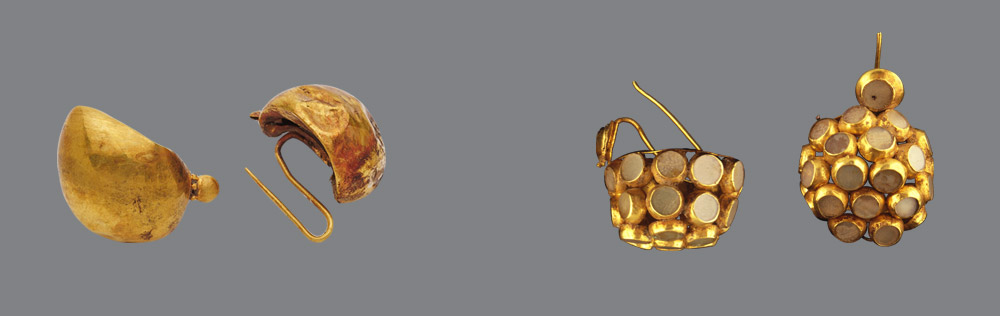

To what degree was gold and silver jewelry considered a luxury, and was luxury of this form reserved for people of high status? While there is no question that gold was highly valued, its malleability also made it suitable for creating less expensive pieces of jewelry, such as the gold foil hemispherical earrings or hollow finger-rings and bracelets. Thus, less wealthy women might acquire jewelry similar in form and style to the pieces worn by wealthier women, but within their own budget.

Is there a way to distinguish between everyday items of jewelry and pieces worn only rarely? At Oplontis, Herculaneum, and Pompeii, finger-rings and earrings seem to have been worn on a daily basis. In contrast, necklaces were stored, perhaps to be worn on special occasions. The theory finds support in ancient texts. Pliny the Elder, for example, disparaged the emperor Caligula’s wife, Lollia Paulina, for attending an ordinary betrothal party adorned in emeralds and pearls worth 40 million sestertii. Interestingly, Pliny did not criticize the cost of Lollia’s jewelry, only that she wore it for an occasion that did not warrant such finery.

Jewelry and Personal Identity

Items of jewelry that were worn at the time of the eruption were most likely personal possessions that say something about the wearer. In contrast, those found in bags and boxes may represent the person’s portable wealth—such as a family’s collection, savings, heirlooms, or dowries. The individuals who were wearing jewelry at the time of the eruption would have chosen those items at least in part because they expressed something about their social standing and personal tastes. Unlike statuary, elaborate wall paintings, and grand architecture, which only the wealthy and powerful elites could afford, jewelry displayed the personal identity of Roman women as well as men of all social classes.